Logic & The Unconscious - Expansion

The third and final lecture in this series zooms out to look at tactics and concepts that can be useful in practically planning a book length project including structure, pacing, momentum, & more

Other earlier posts in this series: Generation Part 1, Part 2. Revision Part 1, Part 2.

For this final lecture, I wanted to focus around taking that framework and energy and aiming to expand into a larger project from it, or beginning to think about how a longer project might be put together from the kinds of things we’ve been talking about. As fun and fresh as work on shorter forms can be, I’ve always found I got the most out of this kind of approach in making it extend across a project that spanned months, years, which might seem antithetical to the notion of curating intense time and space in which to work, but in the same way that a draft generated in a week depicts an idea of who you were and what you were involved in during that window of time, so too does one across the phase of life something like a novel or novella might embody.

This week’s lecture will tend a bit more toward the practical side of writing, as well as the framework and ongoing architecture of working on a longer project of this nature, which hopefully you will inspired to begin and continue within long after this class is over.

WHEN

How does a book begin? It’s certainly arcane science, and one that pends more upon what it triggers in you going forward than it does as a qualitative piece from out of the gate. As with writing shorter texts, you might be triggered into exploration by a single image, sentence, an idea, which from the first words you type continue to fuse together the next line, delving deeper into an idea you might have very little understanding of how it is going to expand into a larger text except by taking small step by small step.

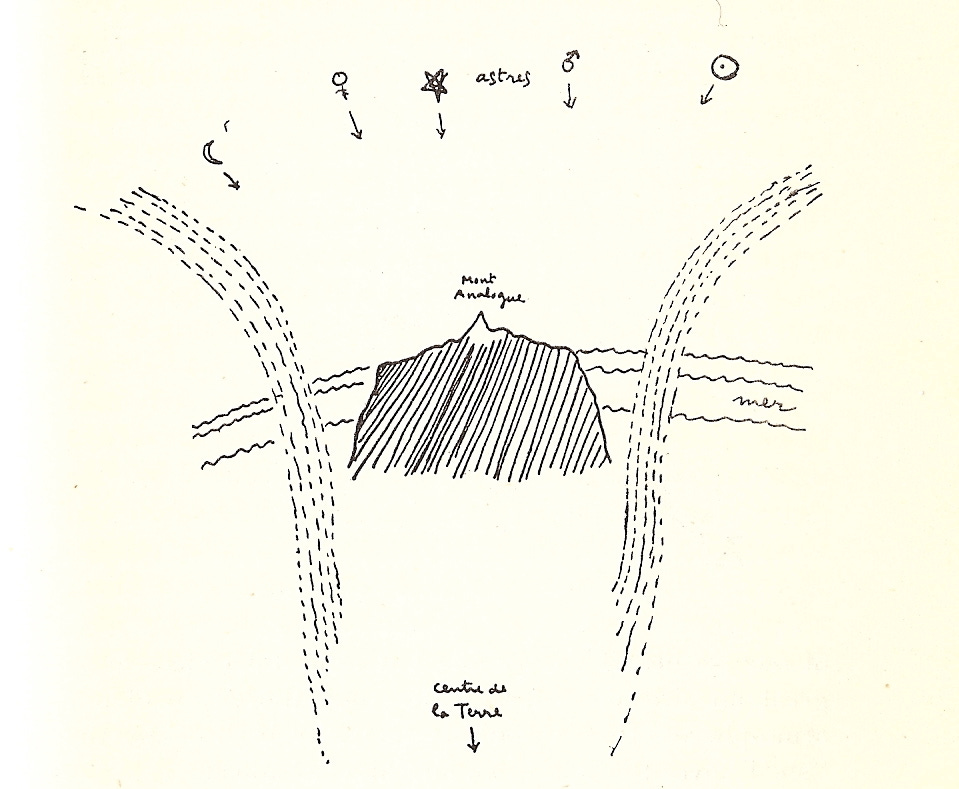

This is why when writing a longer text I usually try to give it some kind of shadow-body before I begin (or in the early stage of writing, where you feel you are onto something larger, but aren’t sure how). There are countless ways to do this, of course, and most of them are arbitrary, and might be abandoned along the way as you figure out where you are really going, though having some kind of outside pressure on the process to me always helps keep the momentum and continuity of the text to remain beholden to itself.

Some ways to frame a book outside the book:

1. Time: You give yourself a specific amount of time to write the book. Perhaps you plan to write everyday for ten hours every day, for eighteen days and when you are done, you have the body of the book (or, more realistically perhaps, you write for three hours every morning for nine months; but exactly nine months). You most likely won’t have the final draft of the book, or even all its pieces, but by setting a time limit in your mind, you can remember by momentum the kind of pacing required, where the book should be at given times throughout. “I’m on the 12th day, I need to start tying some of these things together, making resolutions, toward an end.” “Two days from now this story will be ending.” Etc.

Time doesn’t always work this way with longer timeframes, as you can never be sure what days will look like throughout a year, and life happens, which is why when I’ve used time constraints in the past I’ve done it in a constrained, intense setting, where I was able to close myself off from the world. But certainly plenty of books have been created by the longer method (Faulkner, Allemann), which almost requires a more symphonic approach, and changes completely the nature of the composition.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Dividual to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.