Logic & The Unconscious - Generation Part 1

First in a series of posts sharing my 2017 lectures on rapid, intuition-based prose drafting that focuses on structure, spatial environment, framing, and the body over more traditional literary tropes

From 2017-23, I ran an online workshop for the now defunct Litreactor titled “Logic and the Unconscious.” My primary goal for this class was immersing students in a style of drafting that focused on creating structures and constraints that then facilitate the rapid and intuition-based creation of prose that relies on image, language, and ideas more so than character, plot arc, and other commonly taught tools for writing. I also wanted to make students aware of the effects of their environment and consumption practice on their work; in other words, how what you’re putting into yourself can greatly effect your output in immediate ways.

Over the years, I’ve also shared my lectures from this class with clients for my private bootcamp classes, which often focus on writing a novel or novella-length text in a matter of months. I’ve found that this mixture of improvisation and exploration often results in surprising new elements of writing that whether they end up manifesting in a finished document can unlock weariness to tropes or ‘writer’s block’ where necessary.

Personally, I have written multiple novels in very short periods of time by using variations on this method, very much in styles I would never have considered without the mindset. Even though my approach to fiction has changed quite a bit since I wrote these notes, I still find the skills and concepts they bring into play very useful even in longer timeline approaches. So, in the spirit of making the class materials available to subscribers, I’m going to break the relatively lengthy lectures up into a handful of posts and share them here.

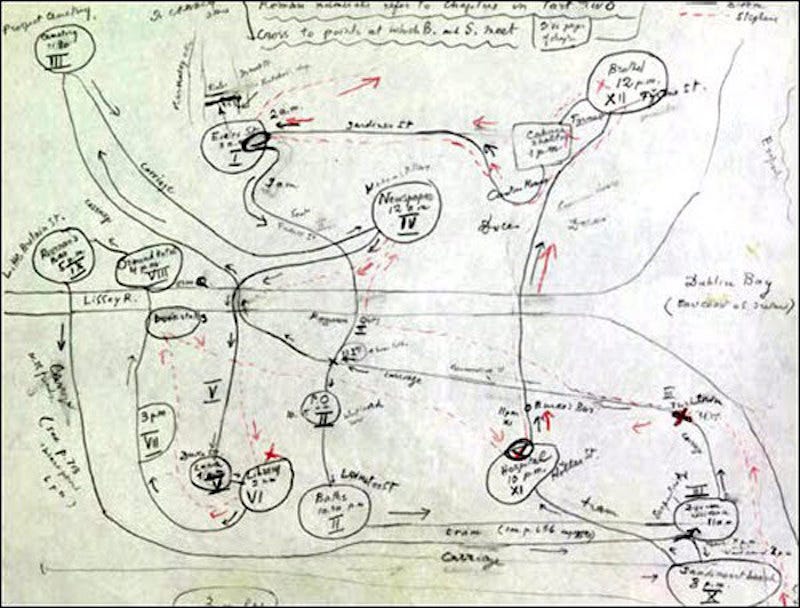

This first post, beyond the break, contains the first half of my lecture on ‘Generation,’ covering considerations of the notions of Space and Frames in writing fiction. It provides some examples from the Oulipo and my own writing; the second post will contain notes on Approach, Modular Thinking, Size, and Endings, as well as an example assignment in which some of the ideas can be put to use. Subsequent lectures will cover topics related to Expansion and Revision, as well as some related reading lists.

GENERATION - Part 1

My emphasis for this lecture will consist of looking at a specific manner of writing I’ve spent a lot of time with over the years, in which we place emphasis on writing a first draft fast (perhaps as fast as possible), without planning, plotting, or worrying too much about where you’re headed or how. This approach will be different than the normal concept of “stream of consciousness” in that despite its associative generation and reliance on image and language to develop text, we will pay close attention to the framework in which that streaming happens, and particularly how to route it as we go. Then, next week, we’ll get into what to do with that raw document in the editing process, which for me is often where the “real work” mostly gets done. A fast draft should serve as a scaffolding, one full of real spirit and blood, full of surprises that you can continue to tease out and develop in revision, as a reader. Not everything we write in this manner necessarily will have a future purpose (I’m a big fan of throwing stuff out), but each time we write, we’re developing, burning away water, getting closer to the thing we really want. It’s an arcane science, but one infused with joy, exploration, explosion, becoming.

With that introduction aside, let’s start digging in on more practically on what I mean.

SPACE

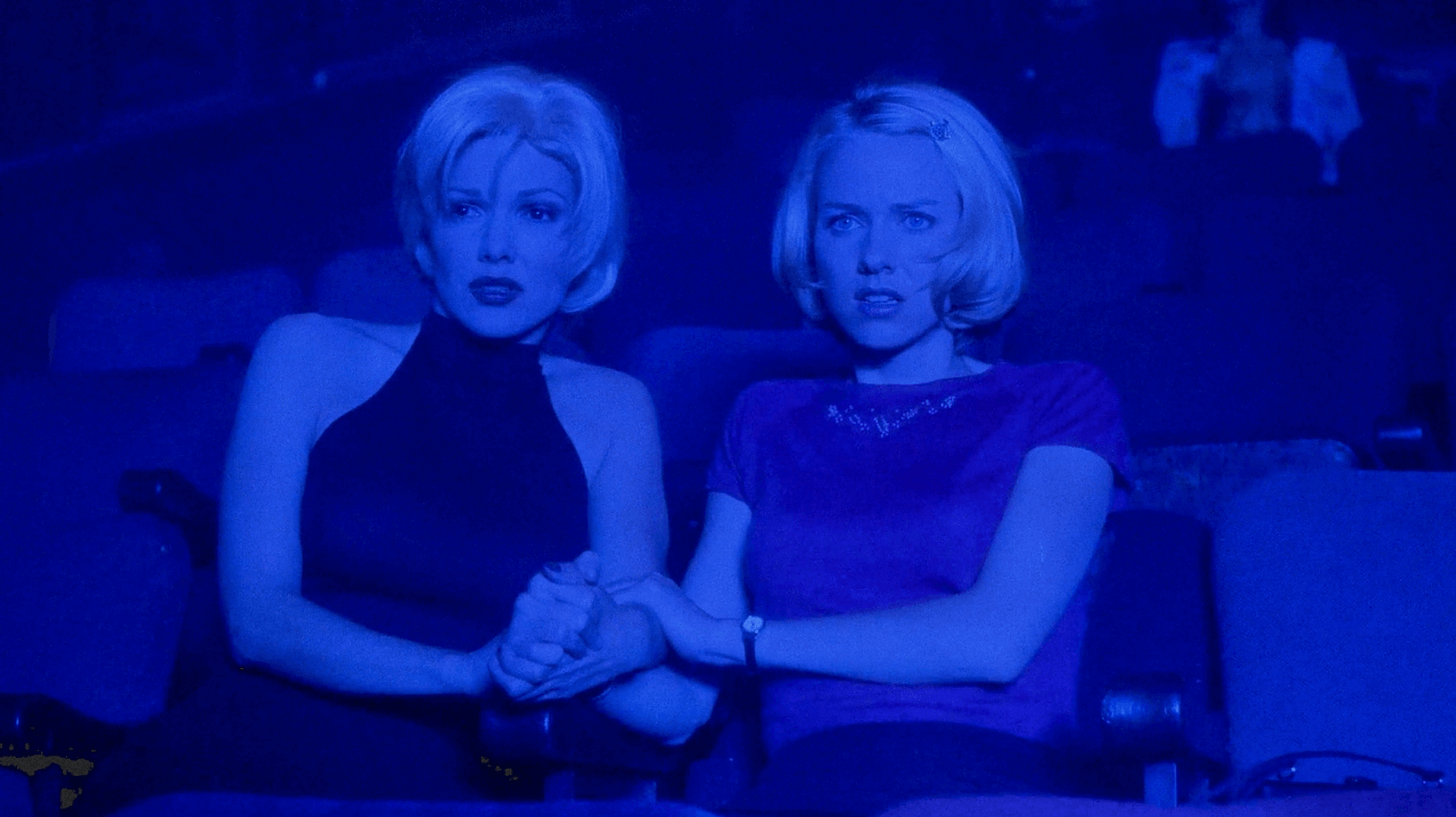

The first part of what I want to discuss in getting started, I’ve called ‘securing the mindstate,’ which sounds out there but also feels important to me, in that looking back, often what embodies or produces great writing in retrospect has bounds, contour, texture; it embodies a state of you were at the time (which always changes, which is why so many people hate reading their work in looking back) and where you were at the time, both temporally and physically. We are, as writers, and as humans, continuously surrounded with information, most of which we disregard as a manner of survival and attention, but too often it seems like we like the streamline around us describe itself. You are at your desk writing, and a car outside passes playing a specific song, and you hear that song and the language, the sound of it, interrupts you, changes your outlook, even if in a completely minor way. Or you’re reading a certain book or watching a certain movie the night before you write the next page of a book you’re working on, not realizing how something about its plot or color or soundtrack put a remnant in an idea in your head, changed the way you think about something; again, this doesn’t have to be a major change, but can be an intuitive one, an emotional one, one so small you’ll never quantify the way it’s slipped into your work.

Think about how differently you might write a paragraph having just eaten an entire plate of beef lasagna, versus how you might write it drinking only pineapple juice for an hour, versus how you might write it standing in extreme sunlight for four minutes, not thinking of anything. The decisions that you make choosing each next word, and how the sentence that word takes part in feeds into the next sentence, the gap between paragraphs, pages, etc., each are all as important as any of them. So why aren’t we paying attention to these things (as much as we can at least?). Why aren’t we controlling them, using them to our advantage, or at least streamlining them toward a direction that might make our writing go a more particular direction? You could go insane trying to limit these factors, of course, or to diagram them, so instead of trying to nail it all down, I’d instead ask you to be aware of yourself when you are preparing to write, and in the writing, and in the time between (esp. when writing a longer work like a novel). I’d suggest, too, to imagine steering yourself during these periods of germination; listening to a certain record while running or driving ‘just because’; selecting media that will expand your vision or closely attune you to certain feelings (even if you don’t know what those feelings are; even better!); moving through a room a certain way back to your desk; talking to a specific person at a certain juncture in the writing (their language is going in you also); what website you have open on the screen beside your word processor when you take a break and click over in a pause (a wiki about an artwork that has a certain aura you admire; a page of current events that define a present situation, and so a mood; anything and everything; so on and so on. There are a billion ways to influence who you are and how you feel at any moment, and you can’t have any of them back. You can only have the sentence that you make inside that moment, and the object that is germinated in the wake of that sentence, around it.

This doesn’t have to be a hard and fast thing, nor even one you try to constrain as much as be aware of, feel; these influences at most will often only be oblique, a mood, a passage; anybody reading the work outside yourself (and even for you, later) should likely have no idea of these associations, how they inform you, the way the work unfolds amidst them (as in the end we are creating a world parallel to the actual world, not bound by or even directly amidst it). Most likely the most direction controls you’ll have in this way while writing might be something like reaching a certain point in your writing during the day and stopping (the flow of which we’ll discuss shortly) and just think “I want to watch Fellini’s Satyricon tonight; I don’t know why,” and perhaps that occurrence will change the way you move to the next page differently than it would have before. I can say that in allowing curation of your terrain to infect the work and its intersection with your stream of ideas as you write, you will rarely run into a feeling of ‘writer’s block’; you will always have somewhere to turn, there will be contour.

Now that we’re thinking a bit about our surroundings, and so our mood, let’s start thinking about actual writing.

FRAMES

Before we get into writing as language, I want to think about the frames in which a work is written. For some people, traditionally, this might be drawing out a plot diagram of a book, which they then use to know exactly what to do from chapter to chapter, page to page. For me, this plot-centered process is nothing but smothering; it defeats the ability of magic, of the unknown, of not knowing where you are going until you get there are yourself are surprised by where the language took you. More often than not, in my opinion, if you are yourself not surprised by where your writing goes, your reader won’t be either (there are certainly ‘masters of plotting’ that prove this wrong, though in general, at this point in the life of the novel, I’d say the odds are against you; and better yet, there is no need!).

At the same time, though, too little direction often comes off just as pat; we’ve all heard plenty of word salad or ‘insane’ work that never tries to come together, never tries to build or invoke logic; and that kind of work can be great too, when done well or in the right way, but in these exercises we’ll be looking at a kind of middle ground between chaos and logic; just enough structure to allow something sublime to burst out of an unexpected patch of land.

So how can we provide a structure for what we’re writing that doesn’t constrict too much, and instead enables magic, by giving it a body to flood into? There are so many ways. It can be assessed or it can be arbitrary. It can be process-oriented or it can be abstract. It can be historically-bent or it can be based on a dream, an object. I’ve tried a lot of different ways to provide framework for a project before I begin over the years, and each one is different; some don’t work at all, some get changed after you begin, some allow wonderful execution that in the end has no oomph behind it (another exercise); but some become the guidelines of fertile ground, a way to understand pace as your proceed, and to sense the walls of where you’re going as you go (imagine a video game in which the world is not exposed to you but in a small radius of lap, mapping the world behind you as you go).

Some personal examples of frames I’ve used to write a text:

- by stealing the structure of a famous novel (for instance, it must have five sections, each of about this certain length, with this general particular POV or angle ascribed from it, without direct relation)

- by setting exact word limits on each paragraph (for instance, the first paragraph has 7 total characters in it, the second paragraph has 77 total characters, the third has 777, then 7777, then 77777, and so on (obviously this example produces an extremely specific kind of text))

- by using a list of random ideas found in another place (for instance, I once stole the frame of an abstract ‘screenplay’ by the composer John Zorn that consisted of a list of 250-ish items, then wrote a paragraph with the idea of each item in the list in mind, one after another, chaining them together logically as I went but otherwise only influenced by the idea or image or texture of what the screenplay provided) (a list so concrete isn’t necessary however; it could just as easily be generated from a list of all the proper nouns you find in a favorite book, or a stream of colors you write down on your own, based on what you see letting your eye move from one point to the next in the world around you on a walk around your block).

- by finding a child’s school ruler on the ground outside my house that had 7 shapes imprinted on it, a random design, and using the order of those 7 shapes to represent the tone of 7 different chapters

- writing alongside the playing of a specific record, without editing, responding to the music in tone but never describing it; utilizing the mood; also have done this writing while watching a film on mute, taking visual cues from what appears and applying them into my own text’s approach; or not on mute, using both sound and image at once

- more improvisationally, by making up titles for each small scene as you go, almost without thinking, blurting the words out, and then trying to write a scene that both fulfills that title and makes sense in the structure of what’s come before it (more on this later)

- Donald Barthelme used to give his students the prompt of (something like) ‘go home and read Ashbery’s Three Sonnets, then begin to write in response while drinking from a new bottle of red wine. Keep writing while you drink all the wine.’

And so on. There are literally endless ways to generate the shape of something’s body; and all you need is some kind of shape. The shape doesn’t have to do anything other than be a structure you aspire toward, allowing constraints of direction and an inspiration of tone to hold in place as you move forward sentence to sentence. It’s meant to be arbitrary, a guideline that will shift as you go forth, and perhaps even become left behind as in the process you figure out after the fact where you are meant to go. Many use ekphrasis (the description of a work of art) to create something new out of a prior object, and this can certainly be incorporated into the routine, though more so we’re hoping to use it as a guideline, a pre-made form that we can fill into, and perhaps reform in our own way, interrupt. Constraints are designed to be broken as they must; but they also force you to go places in your logic that you might not have without any definitions set prior.

For your exercise this week, I’ll ask you to steal the form of something else, literary or object, in any way, and use it as a structure, a beginning from which to spread. Obviously the framework of a novel or novella will be much different than one used to write a very short text, as we will be doing, so that’s all the more reason to get weird with it, try something out. In week 3, we’ll aim at how to extend this practice into a larger project, if you so desire.

For more examples of forms people have used in a similar manner, check out the Oulipo school, which is overflowing with suggestions of the kind of tricks many novels have been written in using this manner; often without the reader having any clue. Feel free to steal one of theirs, or modify it, or better yet, make up your own.

Now, with mood and some kind of however abstract frame intact), let’s move on to the actual flow of the writing.

—To be continued in next post.