This is continued from my earlier post on films 13-7.

Twin Peaks Season 1 & 2 (1990-91)

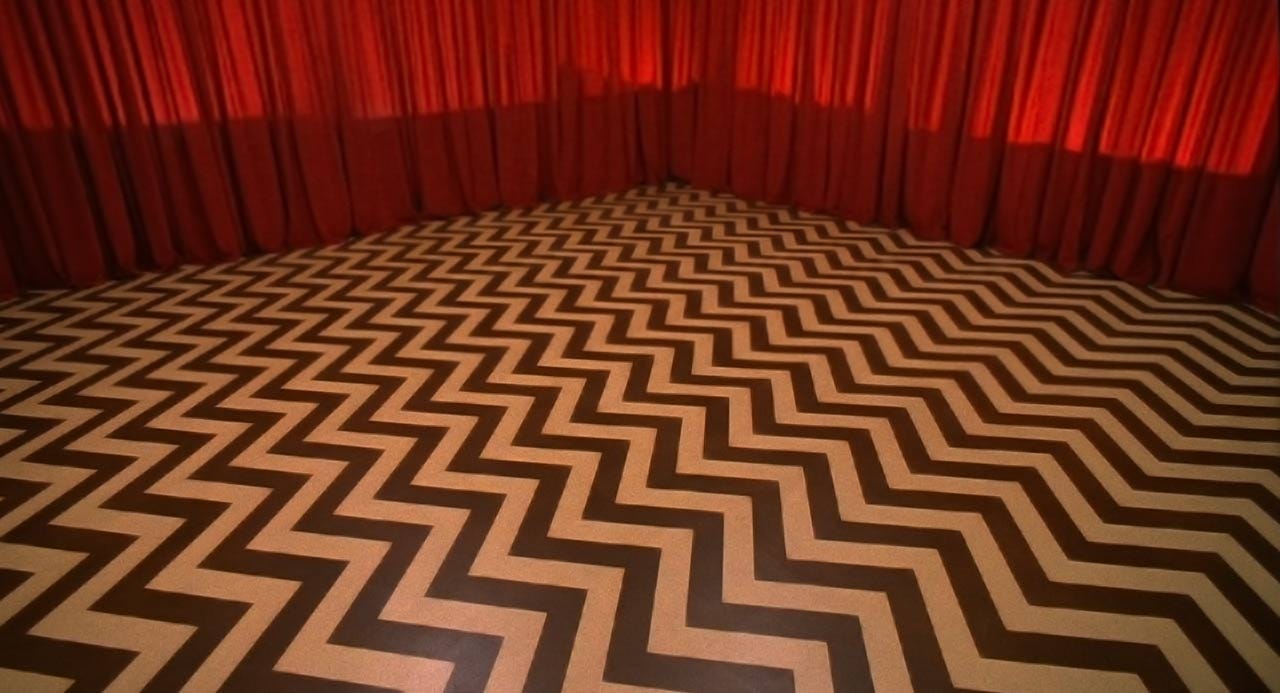

Without Twin Peaks, and in particular its unleashing to a wide TV audience, the work of David Lynch would be a very different entity. It birthed into the mainstream a flood of imagery and ideas that had been previously reserved for late night screening and established a rhizomatic mode of narrative that would continue to spread through everything else he ever made. It also expanded on the early notions in Eraserhead of liminal space and how locations can be connected across time through film, which descends from dreams. From the backwards talking, to the Log Lady and her cryptic warnings, to the mix of low camp with high surrealism, to the overt reckoning with trauma and terror through the life of Laura Palmer, to the polished charm of Agent Cooper, and on and on, Twin Peaks injected the energy of metaphysical conspiracy into the soul of Americana and never looked back. As iconic as Twin Peaks is, it’s still TV, though, and not every episode of the show hits with the same weight. The best episodes are the ones directed by Lynch himself, and sometimes when his influence thins as the show goes on, there’s a normalizing drag that stretches the show for me from a monolithic entity to a kind of skeleton key buried behind melodrama. That said, the second season’s grand finale, in which the wheels come off and begin to reveal the shadows of the entity that consumes so much of Lynch’s vibe. Easily the Lynchiest Lynch, it’s a miracle this show ever hit the commercial airwaves, and its iconic place in history should have been a license to the entertainment industry that audiences are frequently more robust than you might imagine, given the chance.

Eraserhead (1977)

The king of all midnight movie cult classics, Eraserhead forever holds a special place in my heart as a shift in the landscape of what is even possible to communicate. Composed over five years, and written, produced, and directed by Lynch himself, the film is a masterpiece of DIY ambition, proving that you can make what you want if you are willing to sacrifice the normal goals of perceived recognition that hang around most artists’ necks like an anchor. It is also emblematic of a time when audiences were willing to seek out and sit with material that might not produce definitive meaning or utility out of the gates. Part of the magic of Eraserhead, especially as a first film, is how it haunts, bringing together imagery and textures that clearly fit together, but evade literal interpretation. The lore of the film is perhaps even as intriguing as its content in that way—from Lynch’s slipperiness in explaining how he made the bizarre baby; how its 21-page script served as a cue card more so than a law book; how sometimes between shots many IRL years pass even though the film maintains its illusion of continuity. Not knowing why something hits you, or why you keep coming back to it, trying to hold it in your mind, has become something of a lost art for many consumers, and yet the struggle Lynch faced in order to create it ended up being the beginning of a long career of persistence, one that refuses to explain itself even when faced with the possibility of invisibility—a problem that would follow Lynch to the very end. But the film is as hilarious as it is beguiling, and existentially relatable as it is obscure. Like the world itself, the limits of Eraserhead exist in the viewer’s mind.

Blue Velvet (1986)

If there’s one Lynch film that upsets his detractors, it’s Blue Velvet, which also happens to be his most direct critique of the dark soul of the American project. It goes right for the guts in a way that no matter what you think of the work, you’ll never forget. Jeffrey Beaumont, as embodied by Lynch’s Odysseus of sorts, Kyle MacLachlan, stumbles into the conspiracy of a lifetime as simply as wandering through an overlooked field in his otherwise right-as-rain suburbia, eventually forcing him to reckon with the most iconic of all of Lynch’s “bad people,” Frank Booth, performed by Dennis Hopper in a role that he felt so much for that he convinced Lynch to give him the part by insisting, “I am Frank Booth.” Its also an easily mistaken film, presumed to be content with parading the dark night of the soul and the sickness of the individual, when really it’s a film about discovery, honor, and desperation. As a viewing experience, it’s some of Lynch’s most accomplished and svelte cinematography, again intermingling supposed polar opposites to the effect of creating an experience no other film comes anywhere close to revealing onscreen. As a cultural touchpoint, it’s loaded ear to ear with unforgettable lines—”Baby wants to fuck!” “Heineken? Fuck that shit, Pabst Blue Ribbon!” “He put his disease in me.”—and moments of shock—Frank huffing gas from a mask before doing violence; Dean Stockwell’s unnerving presence as Ben, ft. a duet of “In Dreams” with a stage lamp; Isabella Rossellini’s strange mixture of dementia and sex appeal—building momentum as much from the feeling of being unlatched from the sense of normalcy that binds the country in broad daylight as it does from searing itself into the mind’s eye. Think whatever you want about Lynch’s oeuvre and how it frequently refuses to play nice, Blue Velvet is perhaps the crown jewel of a manner of filmmaking that changes the way we see the world upon its release into the psyche.

A third and final Lynch post, covering my top 3 favs, will be coming soon.

Well, this makes the top 3 clearer 😂

Excluding his TV I’d say his best far and away are:

6. Wild at Heart

5. Mulholland Dr.

4. Eraserhead

3. Lost Highway

2. Inland Empire

1. Fire Walk With Me