David Lynch Films Ranked (13-7)

I thought it would be hard for me to rank my favorite Lynch films in order, but actually it was easy.

I thought it would be hard for me to rank my favorite Lynch films in order, but actually it was easy. In fact, I think there’s only one correct answer.

Though I could write book-length essays about so many of these films, I’m going to limit my comments here toward how they stack up in Lynch’s overall body of work. I’ll also include his TV work and a short film, though obviously those aren’t considered films as films.

More so than even most auteurs, there’s an underlying spirit to Lynch’s filmography that binds them together in incredible ways, establishing an entire universe that is larger than the sum of its parts, and sets the viewer up for an experience of the kind of work that can’t be contained by its own medium.

The Straight Story (1999)

It says a lot about Lynch’s oeuvre that my least favorite is so unusual that it stands out from the rest of his entire body of work. A G-rated Disney film about an older man who drives his riding lawnmower across America to see his brother before his brother dies, The Straight Story is a sweet, uncanny, and easily lovable film that achieves a very different tone than even hardcore Lynch fans would expect. It reveals the warm heart at the core of all his work that often otherwise ends up overrun by the larger and louder effects, proving for certain that though you might think you know what’s going on under the hood, you actually don’t and aren’t supposed to. Of all his films, though, this is the one I’ve watched the least.

Dune (1984)

Technically credited to Alan Smithee, the name directors put on their work when they don’t want to be associated with it, Dune is only sort of a Lynch experience, mainly due to the studios not allowing him to have final cut. Thus, the massive 5+ hour epic he created is reduced to under three hours and feels bizarre whether you’re a fan of Lynch or not. It’s still a stunning and unforgettable film, though, due mostly to the bizarre ways he’d make the story his own and explore images and ideas that no other adapter of Frank Herbert’s cult classic would ever imagine. Most fundamental about this flick, imo, is that it would draw a line in the sand in Lynch’s creative life, setting the bar for him to know beyond the shadow of a doubt that if he couldn’t make what he wanted, he’d rather not make anything. His criticism of the corrupt and pathetic inner workings of the film industry would continue to follow him throughout his work, establishing as the sort of once in a generation maverick that cannot be contained. A stunning work full of imagery we’ll never see again.

Twin Peaks: The Return (2017)

Unexpectedly living up to a promise made in the original seasons of the series, “I’ll see you again in 25 years,” Lynch shocked everybody by going back to the world that made him a household name and extending the story to new dimensions as if he’d never lost a beat. The biggest feat here for me is the fact that he was able to convince a network to allow him to put on air some of the most beguiling and unresolving concepts and images ever shot for TV, outpacing even the original in its willingness to go to the edges of what was already so far outside the box. While overall I found The Return a little underwhelming—lacking the same shock and awe of the original, and sometimes getting so hooked on recurring jokes and outlandish effects that for me at times it lost the vibe—the series remains unlike anything else and is unafraid to throw itself into the deep end of its own ideas and not look back. That said, Episode 8 stands out as one of the biggest triumphs of the series, and it’s a huge gift to have so many hours of incomparable cinema to digest for years to come.

The Grandmother (1970)

This 34-minute short, released when he was 24 y/o, is underrated in Lynch’s filmography and as unforgettable in tone as most anything else he did. Many major hallmarks of his work—rich darkness, mutative growth, secrecy and fear, uncanny love—begin right here. There’s something charming, too, about the grainy, student-film feel, a stark contrast to the rich, swank sets and camera movements of most of his work. It provides an interesting lens into how one goes about building the surreal from the ground up, collecting fragments into an emotional core that you can’t help but wonder how it ever found the screen.

The Elephant Man (1980)

One of the saddest and most moving films ever made, this is exactly the effect you want to see when a major artist is hired to adapt a potentially commercially viable narrative product. Even if you’re not a fan of Lynch’s shtick in general, it’d be difficult to have a heart and not be moved by the depth of his ability to depict the titular character’s experience of torment and pain as a freak among men. Even underneath the strange prosthetics and make-up, John Hurt gives the performance of a lifetime as John Merrick, exuding a physically palpable experience of horror and empathy alike. There’s kind of no one else who could have brought the same amount of candor to such a difficult story to have to abide. One of the great adaptations of all time, if also one of the last instances Lynch would bother with trying to work with material that come from anywhere but his own imagination.

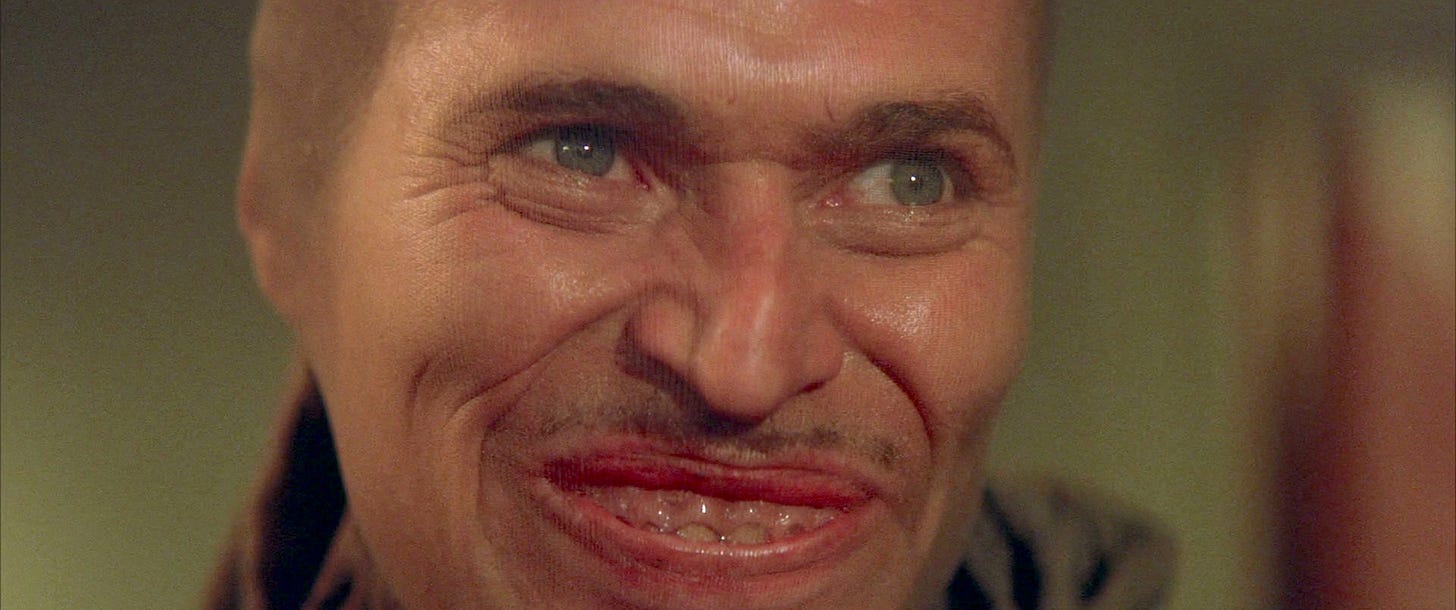

Wild at Heart (1990)

Here’s where we really start getting into the films that make Lynch Lynch. Though its technically an adaptation from the Barry Gifford novel, co-written with the author, Wild at Heart goes extremely hard at breaking open the central narrative into innumerable splinters and shadows, thereby creating worlds within worlds that will continue to ooze out from the parts of the film we think we understand, into the unpredictable pathos underlying its surface. Laura Dern and Nicholas Cage make an incredible pair, campy in their lovey-dovey-ness, but also unhinged in how they defy and overcome what the film sends after them. As a love story, it’s a cult swooner, full of iconic lines and choices that make the film feel larger on the inside than out; as a horror story, it pushes the edge of Lynch’s ability to build tension and menace under the guise of the everyday. Even with limited screentime, Willem Dafoe’s embodiment of Bobby Peru adds to the list of spectrally terrifying bad guys that will populate the Lynchian universe like an army of henchmen embodying the dark. Whether its Diane Ladd smearing lipstick all over her face and cackling like a witch, or Cage’s Sailor Ripley waxing Elvis-poetic about his snakeskin jacket, Wild at Heart is unforgettable, and demonstrates yet another side of Lynch’s repertoire that defies explication.

Lost Highway (1997)

Lost Highway feels like an existential film, and one that reflects most deeply Lynch’s love for Kafka. Full of loose ends, infinite hallways, errors in time, split personalities, symbolist objects, and metafictional tropes, it’s easy to get lost in the world the film presents versus the way it inhabits the unconscious, crossing all kinds of wires as you watch. The first half of the film is some of my favorite tension building ever, as we are subjected to mysterious provocation after provocation, wandering through rooms that seem like they lead to places we never get to see. There’s a ton of camp here, though different even than the kind found in Twin Peaks—instead, it’s Richard Pryor, appearing late in his illness; it’s Robert Blake with a powdered face and a brick-sized cell phone; it’s Marilyn Manson in a subtitled snuff film that makes Bill Pullman’s head spin; it’s Robert Loggia as a thug beating the shit out of a tailgaiting driver. Most of all, it’s the late 90s, reflecting the end of an American era before the internet, almost like a mystery in which we watch the soul of our country slip between the cracks in its own mediation. There’s a really evil sense to this film, one that even the way it builds toward a reckoning doesn’t quell—instead, the film ends with us speeding away into the darkness, running from cops toward nothing as it seems. Not necessarily Lynch’s most cohesive film, it’s definitely one of his most disorienting, and one that find myself continuously coming back to in my mind as a door that was opened and never closed. I wouldn’t argue with anyone who said this is the most Lynchian film of all, peppered with some of his most indubitable textures and moments. It’s the kind of film we’ll never see anyone try to make again.

To be continued…

I too am a big fan of Lynch. Enjoyed your post. Two nights ago we watched Jane Campion’s film “Sweetie” and I was wondering if you had ever seen it? Very odd and disturbing. She really got to the heart of a family’s mental illness.

Omg, The Elephant Man. Agree. Killed me as a young person.

Wild at Heart is my #1. :)

Then Mulholland Drive. Those two are pretty close for me.

Love Blue Velvet, Lost Highway.

The Straight Story is special in its own way although I rarely watch it.

I liked Eraserhead and Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me.

Wasn't crazy about Dune.

I had a hard time with Inland Empire, it felt like slogging through Moby Dick (sorry, I think that is your favorite Lynch film?).

Love your posts, I always learn from them.