What is an 'Internet Novel'? 2 (b/w Povel)

Ten notes on Geraldine Kim's 2005 work of hybrid memoir, poetry, and fiction that remains unlike anything you've read

This post continues from this previous post about DC’s The Sluts.

Povel [Fence Books, 2005] gets its title from the portmanteau of poem and novel, which is a nice tidy way of pointing at how this book both has an arc, characters, settings, and other traditionally novel-oriented features, but generally operates chaotically w/r/t flow. This is NOT to say that it contains stream-of-consciousness writing because it really doesn’t, despite the tendency of more between the lines thinkers to label anything that isn’t coherently sequitur the product of navel-gazing, when in fact it takes a serious amount of focus and crunch-power to pack as much information and ideas into one text as Geraldine Kim does on every page of this book.

If there’s any singular feature about the ‘internet’ novel in general, I’d suggest it is exactly this quality—a kind of kitchen sink/hyper-dense approach to presenting the reader with information that often feels like continuous digression but is actually the product of being more on-point than your average show don’t tell-er. Like being online, reading becomes more a matter of how you think about what you’re been given, and how you choose to navigate through it, and thereby the meaning one glean’s from what the author’s laying down is more a product of their excess of style than it is an incongruency or lack of direction. Like Megan Boyle, Kim has so much style she pretty much invents a new way of thinking on every page, and thus reading her feels like an endless voyage inward, limited solely by the reader’s capacity to keep up.

You can’t write an ‘internet novel’ and be boring, is basically what I’m saying, and yet a great and true ‘internet novel’ also by dint contains countless banal and everyday subjects and objects all wrapped up in the same straightjacket, with nowhere to go but into the feelings, machinations, ideations, and various other forms of psychological detritus that populate the ‘world of the internet’ like an open-air mall. In this way, DFW’s desire to try to write a novel about the most boring shit in the world—taxes—makes sense when seen as a follow-up to Infinite Jest, which imo is more of a late-stage TV novel than necessarily an internet one, though IJ does bear many stripes of both. I have a hunch most people who have written an ‘internet novel’ had a DFW phase at some point, as he limns the possibility and kind of embodies the serious geek soul that animates one’s will to write at all.

It’s basically impossible to write an ‘internet novel’ without being meta to a significant extent. As a vehicle for experience, the internet changed the world through its ability to simulate reality as information while simultaneously removing the need of the user to participate. Far from being a dickhead’s maneuver meant to show off their brains (which they nevertheless do have), meta tactics in fiction at least to me feel fun, like dick jokes in a valedictorian speech, and also serve to undermine the reader’s ability to pretend they’re not participating in an aesthetic event. A ‘novel about the internet,’ rather, would tend to miss this distinction, in that it mistakes the internet as an interesting topic all on its own, worthy of treating like nature or people; an ‘internet novel’ knows this is bullshit, and that the internet is just as much a mouth of hell as it might be a wellspring for insight.

Right out of the gate, Kim smashes through all the paper tigers you might have envisioned for what even a hybrid poem/novel might be. The book opens with an introduction from Lyn Hejinian (whose lyrical influence as all over the thing), who also includes the Povel’s alternate title for all to enjoy, a four page run-on sentence that begins: I Wish This Text Was the Winner of Some Award or Worth a Skim-Read At Least or Who Am I Kidding? The Only People That Will Read This Are My Family and Friends or I Don’t Even Think My Family Or Friends Will Read This So Maybe Just My Ex and My Poetry Teacher…. Such unwieldiness, while intentionally unruly and wink-wink in context and out, point to another aspect of the ‘internet novel’ that feels as vital as any, being the attempt to build a book that contains more than it possibly can. When it began, the internet was a conceptually infinite space, esp w/r/t text, where the only limits to what it could contain were essentially one’s imagination; an ‘internet novel’ that has forgotten its own origins, such as those published in the 2020s, might tend more toward social media, advertising, surveillance, and misinformation, but the true soul of the ‘internet novel’ lies in its concept of the network, reflecting intersections of rhizome upon rhizome spread across virtual space ad nauseam. Thus, before we’ve even gotten started, we’re up to our necks—and this is how the ‘internet novel’ likes it.

Following the intro, which draws on some theory before quickly wrapping up, Kim offers a "‘Transcript of Geraldine Kim’s Acknowledgement Speech,” which reveals itself via asterisk as ‘Jim Carrey’s Academy Awards acceptance speech’ rejiggered as a thank you list of sorts for the people who helped her make the book (DFW is on the list). Then she reprints the already mentioned full alternate title in bold, which takes another 4 pages, followed by a wry epigraph, again pointing inward:

It’s a good joke not only for the diminishment of expectations, but the vastness of the white space after so much text, which feels meaningful in and of itself. Lastly, she provides a cast of characters, which are basically her extended family, and the instruments that represent them, noting “Povel was first performed/recorded October-December, 2003 at New York University, New York and Boylston, Massachusetts.” Another meta joke, denying the media its singular form by way of making up a rumor about one’s self, but I’m guessing that the time period mentioned is probably the period during which the manuscript was written, which I think also points to another frequent feature of the ‘internet novel,’ being the spasticity of its invention. Perhaps the reason we’ve yet to see a systems-style internet novel on the par of the very visible doorstop is a product of the necessity that it arrive in something of a frenzy, containing equal parts improvisation and realization at such a pace that even the most willing accomplice should have a hard time keeping up. Rather than being dense in a postmodern sense, it is dense by dint, the way a day is, depending on how you parse it.

The problem, then, with identifying the internet amidst its own field of madness is that we’re living inside it and we can get out, but we don’t want to. Sound familiar? If so, it shouldn’t be surprising that mental health issues such as depression, suicidal ideation, obsession/compulsion and the like go hand in hand with other more literal subject matters such as existence, relationships, and experiencing change. Were it simpler, rounder, more coherent, it wouldn’t be the fucking internet, now would it—or at least not the version we’ve ended up living with like a hidden monster in every room of the house.

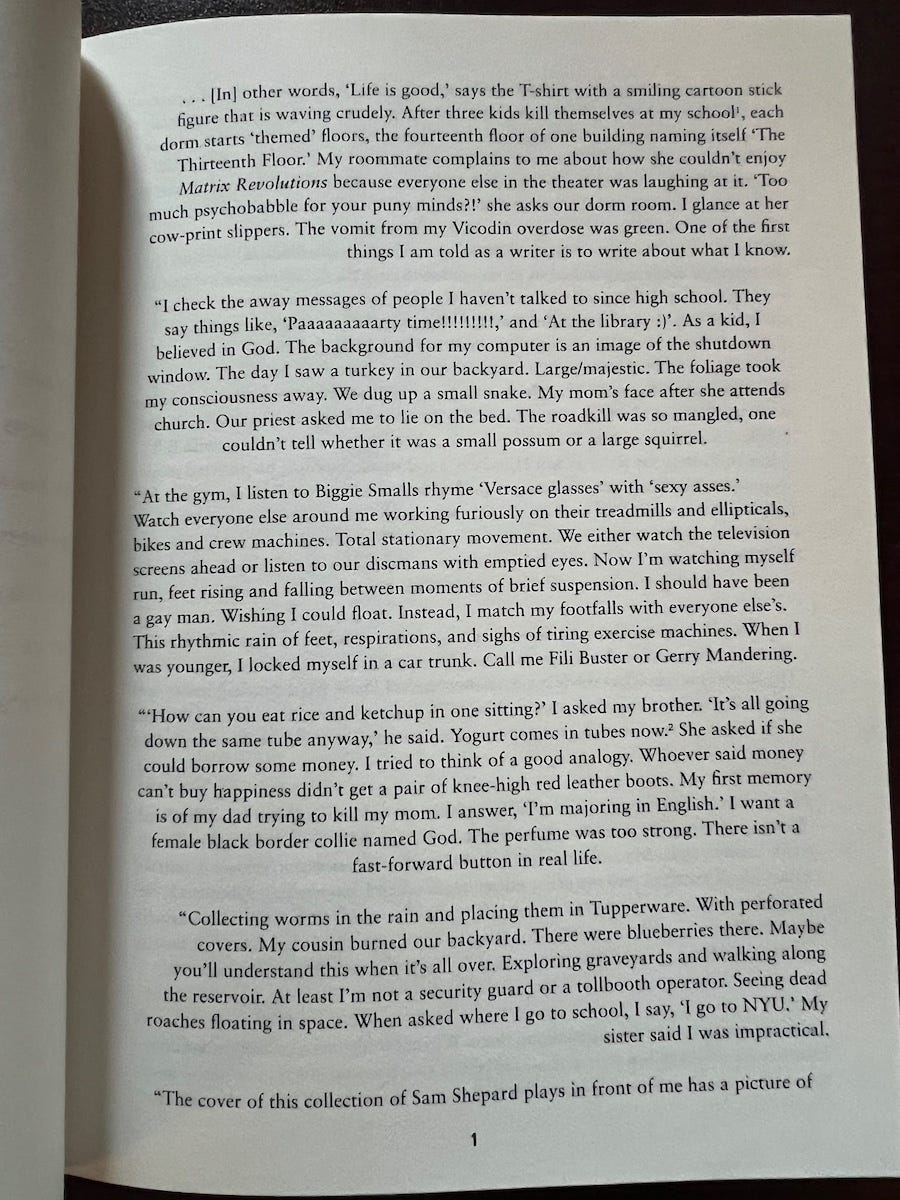

The resulting texture of such a set-up is a bit like taking part in a very personalized form of surveillance, one in which the author, or user, ends up reporting on themselves to the brink of death. The vast bulk of Povel, unlike the multiplicity of its introductions, takes on an extremely monotonic form, the same throughout its 113 pages until you reach the footnotes. After kicking off with an ellipses, each page is broken into partially lineated paragraphs between 5 and 10 lines long. Each paragraph begins with an open quotation mark that never closes, including on the last page of the book, sustaining a feeling of being monologued at in rapid sequences of thought that looks staccato but feels smooth. The sentences are often brief and sharp, using only exactly as much space as they need. Sometimes the sentences link together to continue a thought; other times they are more singular, reflecting an unconnected sentiment that may or may not recur. It feels a bit like reading a diary, though not one written for the author—more like a record of events chained to the thoughts that make them tick. Kim constantly references music, films, celebs, businesses, and quotations in the same way one might online, providing observations on cultural entities right alongside admissions of her own feelings, ideas, desires, and the like. Less so than telling a single story, we’re being told thousands of tiny stories, which once assembled reflect about as directly as you could imagine what it might like to exist inside the author’s head.

The effect is hardly discursive in this fashion; it actually feels more real and relatable—and hilarious and strange—than most realistic novels that attempt to construct narratives out of such strands, as if to ply the reader to their side. The great joy of reading Povel comes from its voice, but not in the way that voice is usually paraded around as a brand, or a plot device hidden in tone—it’s because Kim, as a creator, is singular and exciting in the same space. Momentum builds both from wanting to see what she’ll string together next as it is from the way the stacking paragraphs course and recourse across the novel’s finite timeline. We see flashes of interactions with continuing characters alongside the narrator’s sentiments about them, often as transitional in context as the whims that populate our thoughts from moment to moment, maintaining fluidity while also feeling routine thanks to the structure that Kim uses to define the way she sees the world from page to page. You could open this book to any page and find food for thought packed in alongside uncanny images left hanging, declarative statements about the people in one’s life alongside instructions to the author on how to edit her own prose, mini-dialogues overheard alongside eventual culminations of the same energy hours later, and so on. Essentially, the book neither truly begins or ends, in that fashion, but rather keeps stacking on new links and fragments of content as if time itself might never stop—until it does. It is exactly this boundlessness, pressed into containers that almost too obviously force compression on the whole, that makes Povel such a wonderful experience—not only as an ‘internet novel’ 2005-style, but as a work of art that transcends its own nature. In an ideal world, there could ultimately be thousands of books like this, representing sections of time we can’t get back. In the end, there’s only one Kim.

In closing, Povel provides footnotes, which seem to me an essential part of all ‘internet novels’ in theory, given the way they allow commentary as digression from its own source. Among its exactly 200 units, Povel breaks even that mold, offering an entire short story by Kim, outward references to look up elsewhere what she doesn’t have time to explain, translations from Korean, notes to self to INSERT STORY!!! that remain incomplete, a pissed off photo of Nick Nolte, and so on. Following those, Kim includes a closing page titled WTFHJN (“What the Fuck Happened Just Now”) where the reader can make their own notes about what they think and feel about the book and its many parts, encouraging them to hate it if they want and use additional paper if needed. The very last page of the book is a portrait of George W. and Laura Bush with a cut out of Kim’s face pasted over W.’s, and an author bio that is W.’s lifestory with her name replacing his. If that’s not how you end an ‘internet novel,’ I don’t know what is.

Enjoyed your thoughts on this. I'm a fan too. Ordered it recently to reread.