The Daily Life of an Alzheimer’s Caregiver

Speaking with my mom about her care routine for my father during the middle to late stages of his illness

This webicle originally appeared at Vice on March 14, 2013. Since then, both of my parents passed in relative states of dementia, and support for caregiving has only grown more grim. Information lessens stigma, which is why you don’t often hear.

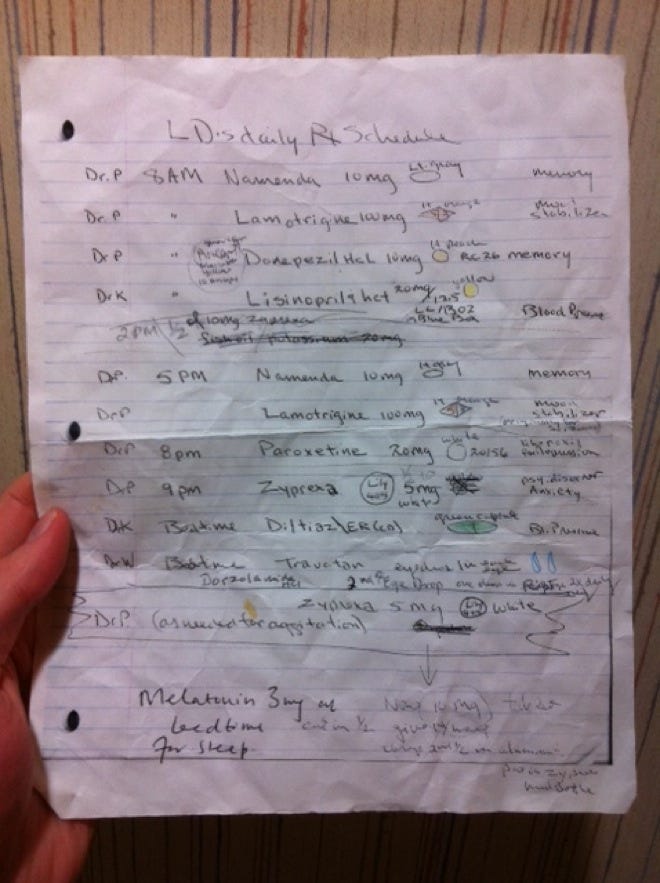

My dad was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s about three years ago. After an extended stay at the hospital and stints in two different rest homes, my mom brought him home to care for him herself. I live about half an hour away and visit regularly, but most nights and mornings it’s just the two of them. For a while he’d tried out several different rest homes, but the conditions there were so depressing, due to over-medication, to the implicit feeling of abandonment, to to just the smell, that finally Mom decided she had to at least try to bring him home, despite warnings that this would be too much stress for her to handle, even with regular assistance. There is an unseen routine in the lives of most home caregivers that makes Michael Haneke’s Amour look like Sesame Street. I wanted to find out what the day-to-day life of someone tasked with keeping another adult alive is like, so I talked to my mom about it.

BB: How does your average day begin?

BB: Usually I wake up before L.D. and get dressed, and I try to get the coffee made and the cereal stuff out. But if he wakes up first, I just get him cleaned and dressed and then do the other stuff.

What time does he get up?

He’s gotten so he goes to bed between 8 and 9 PM and sometimes sleeps until noon. One day I was so tired and exhausted that I didn’t hear him and he got up and went into the den at seven in the morning. He ended up somehow falling, and I found him on the floor tangled up in the chair. But usually I wake up before him and get dressed real quick, because if I don’t he watches me do every single thing and it drives me crazy.

Why does he watch you?

Because he doesn’t have anything else to do. He just stares. And he wants to see what food I’m making.

I know he usually wets the bed at night, even through the disposable underwear. Do you change the sheets after you wake him up?

I take the sheets and the pajamas and the shirt and socks and just wrap them up in that plastic liner that keeps the mattress pad dry. Sometimes if he wakes up before I do he’ll have already taken his underpants off. I get him to the bathroom and have him sit on the toilet so I can get his wet clothes off and wipe him off with HandiWipes.

You have him sit on the toilet to get dressed and undressed?

Yeah, because he might go. And if he’s not bad I can use those HandiWipes and wipe him off and put powder on his back and in his underwear so that it will be dry. But like today he was soaked, and had taken his own stuff off, and didn’t want to get in the shower. He doesn’t like me to bother his pants, and when I mess with them that’s when he grabs my wrists. I figured out that I can reach behind him and underneath and pull the pants down that way. He’s still grabbing, but once I get them down he’ll sit on the toilet. It’s tricky. Once he’s got a hold of my wrist I’ll threaten him. I say, “You’re going to have this hand in your face if you don’t let go of my hand.” [laughs] He knows I’m not going to do it, but… I get really angry because I’m helping him. I try to explain to him, “I’m trying to help you and you are hurting me.” And he’s strong. Sometimes my wrists are red afterward.

He doesn’t realize you’re helping him.

He wants to do things himself. He always has.

Then when you finish with the clothes…

Once I get him in the shower I pour shampoo on his head. Baby shampoo, so he won’t tear up. I used to give him soap and he’d use it but now he doesn’t, so I put on these gloves and put the soap on my hands and just reach in the shower. Of course I get soaking wet—my jeans and everything, but I soap him up and down and wash his head. He doesn’t like that at all.

So after he’s dressed and fed, he mostly just walks around the house all day?

All day. Moving stuff. I have to make sure all the doors are locked. Like today, for instance, when I came in he had the peanut butter out and two steak knives in it. I don’t know why the refrigerator wasn’t locked. I have rubber bands holding down the kitchen faucet because he used to turn the water on and leave it running. He tore the doorknob off the computer room. Basically, he’ll fidget with anything that’s loose until it is destroyed.

But once he’s set up and ready to go in the morning, you can sort of do your own thing, right?

I have to keep checking on him to make sure he’s not tearing stuff up or hurting himself. But I make sure I do something every day, dyeing fabric or sewing or something, because if I didn’t I’d go crazy. That’s the main thing they teach you in the caregiver’s class. It’s like the oxygen mask in the airplane: you don’t put it on your kid first, you put it on yourself first so you can get it on your kid. If you don’t take care of yourself you’re not going to do him any good, either.

Have you noticed any effects on your sanity?

I get on crying jags sometimes. I get to where I can’t think what I’m doing because he’s driving me crazy. That’s when I hit the sewing machine to get it off my mind. Abraham Lincoln said, “I’ve learned that a man is just as happy as he makes his mind up to be.” So that’s what I decided: I’m going to make up my mind to be happy.

You were having big problems with him tearing up the plant in the kitchen, but you were determined to leave it there.

I don’t want him to think he can just tear up everything. I want him to learn not to. For some reason I think he can do more than he can. I believe it’s in there.

You used to spend hours trying to explain to him who you are, or who I am, and then eventually you began to accept that he wasn’t ever going to understand.

I know he doesn’t know who I am. He knows I’m a safe person. And sometimes he’ll call me Barbara. But he doesn’t know. It used to bother me, but it doesn’t now. He can’t help it, and it’s not going to change. And when he does… The funniest thing [laughs] was when he told me… I’d said, “Quit pacing, you’re driving me crazy,” and he looked at me and said, “Well that’s probably your problem.” That cracked me up. He said a rational sentence and he put some thought in before he said it. So I know there’s something in there somewhere.

Sometimes I wonder if he’s actually having a moment when he says something witty or if it’s just an accident.

If he wasn’t thinking it through then, he sure did look like he was. But mostly he ends up talking gibberish. He’s gotten to where now if I say, “Are you hungry?” he doesn’t know what I mean. So I’ll say, “Do you want something to eat?” Then he knows what I mean. So there are certain words that he knows.

Being immersed in this every day has got to be pretty physically demanding, right?

A lot of it is routine now. But the main thing is, if he’s in the room you can’t concentrate on what you’re doing, and if he’s out of the room you think, What’s he doing? You worry about what he’s getting into. He’s broken and torn up so much stuff… and he thinks he’s working. When Tommy [his brother] calls and asks, “What have you been doing?” L.D. says, “I’m working. I’m so tired, I’m worn out.”

Why were you determined to bring him home instead of leaving him in the rest home?

The rest home did him more harm than good. When I went in to see him there the first time they had him in a hospital robe, which he had never been in before, and sitting in a wheelchair. He was drooling, drugged-out. He wasn’t like that at all when he went in. When we moved to the next place they forced him in the ward for the most severe patients because they said there wasn’t enough room in primary. He couldn’t even get to his room because they had it blocked off with patients lying on cots.

They basically tried to turn him into a zombie on purpose so he couldn’t go back home and no one else would want to admit him.

They claim to go from the early stages to the late stages. “We cover everything.” And they do. For $7,000 a month. He was being institutionalized. When I decided I wanted to move him somewhere else they told me, “You can’t handle him.” They were wrong.

Right. As soon as we got him out of there he was immediately much more himself, or at least not drugged-out and pushed up against a wall. Even as demanding as it is on you now, I feel like it has to be less emotionally destructive overall. At least he’s free and not surrounded by death.

I freaked out every time I went to visit him. The only real car wreck I’ve ever had was after leaving the nursing home in Roswell, because I though it was going to be a nice one. I thought I was going to throw up before I left there. People have told me I’m hurting myself by bringing him home and waiting on him, but I’m doing what I want to do. I sleep better now than I ever did when he was gone. He goes to bed early and I can stay up late every night. I play my games and sew and listen to music and relax and have a glass of wine and I sleep like a top. And he sleeps really well. As much as he might drive me crazy, when I think about him in the nursing homes… I can’t tolerate that. He probably wouldn’t know much difference, and yet I feel that he would.

Do you think you’ll be able to continue to handle him as he gets worse?

You don’t die from Alzheimer’s; you die from complications. And, physically, your dad is healthy. He’s probably going to be around a while. And that’s good. But he always said he never wanted to be this way. He always said, “If I end up a certain way, do something for me.” That was back when Dr. Kevorkian was still around. And I would want the same thing, too. But he could never do that to me and I can’t to him. I’m thinking I’m keeping him here as long as I can.

Still so amazing and beautiful. Remarkable the type of things that Vice once published.

I'm glad you are bringing these back. This one in particular continues to feel as achingly lovely as it did when I first read it.