Publishing Field Report 6 – Calamari Press (Part 1)

Notes on how I came to know my first publisher, Derek White, and what I learned in looking back after finally discovering someone who believed in me

Having abandoned my agent in favor of attempting to find a publisher for my first book, Scorch Atlas, on my own, I speedily discovered that soliciting indie publishers, while often more accessible as process, was still no cakewalk. In a matter of months I’d already thrown my hat into as many rings as I saw fit and continued to find rejection—this time from actual editors directly, sometimes detailed and sometimes form. As my shortlist of places I could send to that might get me dwindled, I continued sending the book out to cast a wider and wider net, relying once again on sheer volume to find just one that finally stuck. I kept close track on which press’s submissions windows opened when and prepared to send ASAP, and notated the responses, good and bad, as evidence that despite my lack of landing, I must in some way be making progress by finding out where my work didn’t belong.

In the meantime, I kept writing. Even in the midst of much rejection, I still felt that even if this one never landed, the fact that I’d finally written a book that I believed in was evidence that I could do it if I wished—and having seen already that refusing to accept I couldn’t had allowed me time and space to continue to improve. If not this book, then maybe the next one. Crucial here to point out that I already understood I wasn’t likely going to make a living from my creative work, at least not now. In MFA, I’d met writers who’d written one book and decided if they couldn’t “make it” and get paid, they’d never want to try again—too cruel a system, too much thankless work. For me, though, the challenge itself was part of the thrill, and the more resistance that I met, the more I wanted to prove it wrong, by leaning in to ingenuity, rather than lying down in hopes of finally fitting where I didn’t. This, to me, is more the essence of ‘experimental writing’ than simply defying standards because you can—the experience itself is the experiment, seeking locks for which the many kinds of keys I’d learned to craft might fit, lest they only ever be a key.

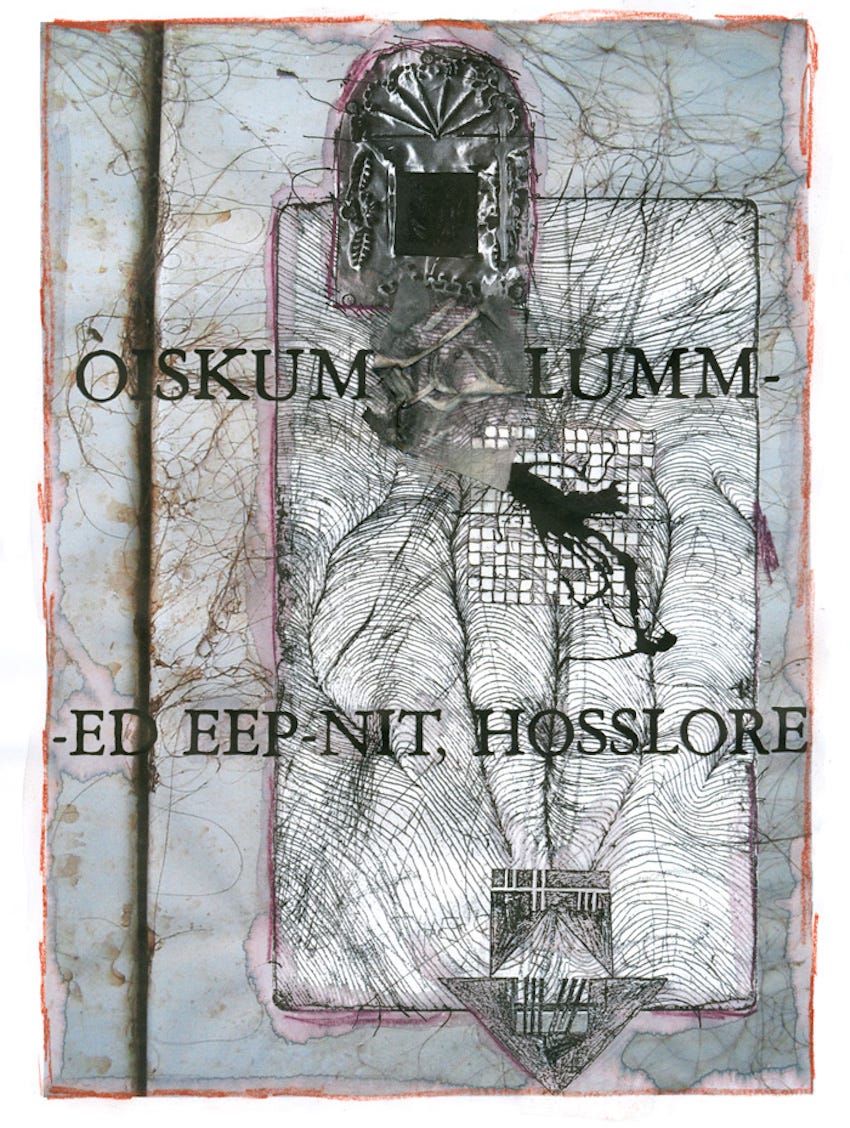

One of the places I eventually sent Scorch Atlas was Calamari Press—a micro venture run entirely by one person, Derek White, who I’d become online friends with after discovering his writing in a web mag and soliciting him to send something to Lamination Colony. Quickly, Calamari had become a bit of an obsession for me, publishing strange and singular work by a whole sect of writers I’d never heard of—Robert Lopez, Peter Markus, Miranda Mellis, Garielle Lutz, David Ohle—but who felt much more akin to what I was doing than most other indie spots. I felt an immediate mystique there, similar to the thrill of uncovering a record label full of hidden gems from another world, more so than a commercial enterprise that might seek to repackage me to fit their means. Each of the books were carefully designed in a strange but singular house style that somehow managed to bring an aura to the wide array of unique authors that they put out. Calamari clearly prized the book as an art object in that way, and for the first time, outside of music, I felt a desire to be a part of something rather than a product on a table who needed professional help to find their place. Here, specifically, was a place that I could see myself, beyond mere wishing, in a way that made me want to realize what that meant. I bought all the books that Derek had published and would continue to do so with each new release, excited to see what other levels were out there somewhere I hadn’t found yet.

That year, I went to AWP for the first time, solely because it was right in my backyard in Atlanta. I had a few friends from my MFA and online acquaintances I’d corresponded with who I knew would be there, but in general I was entirely alone, wandering around the convention center as in a jungle, trying to find lay of the land. I met Derek at his table, dressed all in black selling his books, and found him charming in his unassumingness, how matter-of-factly he slipped right past all the bubbly decorum of literary salesfolk. Derek wasn’t one to waste time following the unspoken rules so much of publishing seemed indebted to beyond all else. Rather than feeling like I was blind chasing a dragon, I felt akin for once, finally putting a face to some of the names I’d encountered through the work first, a common ground. The game was maybe very different than I first thought, I realized, implemented by actual people with lives and tastes, not just big brands. This had always been obvious in music, in my experience, but perhaps precisely due to the lack of physicality literature commands, it had never seem so real until being amidst it, live in the flesh.

Lo and behold, too, not long after that first meeting, Derek asked me if I had a manuscript that he could read. I sent him Scorch Atlas straightaway, thrilled after more than a couple dozen other rejections to have a direct opportunity for the first time, not just slush. Here was the world opening up for me finally, I thought, and all it’d taken was to immerse myself in the process, boots on the ground. While awaiting his response, I walked around on pins and needles but with my head high, like I’d already won—because I had: Someone had seen enough in who I was and what I did to imagine I might have even more left yet to give. That opportunity alone, unlike all my prior research and correspondence, had already made the whole enterprise of publishing seem much more real, like an actually achievable goal, not just a pipe dream needing a lottery-like windfall to actualize.

Imagine my disappointment, then, when several weeks later, Derek said he didn’t think Scorch Atlas was quite a fit. He saw the obvious merit in it, he wrote, but it was perhaps still a little too narrative for Calamari, the sort of thing another press could do much more with than he could. This felt insane to me, at first, in that it was the opposite of what I’d been rejected for elsewhere—too weird for traditional houses, too traditional for weird houses, so where the fuck did I belong? At the same time, though, I understood. I’d written these stories with the aim of publishing in magazines, and despite their strangeness, they didn’t quite make sense amongst the rest of what Calamari did—so close and yet so far, and therein enough to almost make a person want to give up then and there, like if even this spot doesn’t fit me, then what could ever?

Derek was kind, though, and told me I should try him again when I had another manuscript to send his way. He said he felt like we were meant to work together, just not on this, which at first felt like a platitude, letting me down easy, but then became a gambit all its own. Rather than try to send a work I’d written for anyone to such a unique press, why not write something specifically for the case at hand? In fact, I’d already started doing that, I realized, as after finishing Scorch Atlas, I’d started a totally different sort of story that had since grown far beyond a story’s size. It wasn’t finished yet, but now with the idea in mind that someone specific with the power to publish it would want to read it when it was, I felt a newfound source of fire in my mind.

Over the next many months, I’d spend all my available hours working on what would become Ever, which I’d originally thought was another story split off from Scorch Atlas and now had the gas to turn into something else entirely, just like that. The idea that I could be seen made it more real to write as if I would be, even if nothing was really guaranteed. Suddenly it felt instead of like I was writing in the darkness desperate for light, I was now writing with a mission in mind: to make the thing I’d make if seeking anyone’s approval needn’t be a part of the process at all, and in fact, that the very drive of not needing anything but the page itself might be the fulcrum that would launch me forward into the work that would help define me both to myself and to the world. The publication process didn’t need to be marked as solely damning or dreaming, finally, but more so a subsequent extension of the soul-bearing behind it all. Up till then, I’d been so spun by wondering whether I could ever crack the seal that I’d sort of ended up head-assed, thinking I had to trick my way in before I could ever do what I really wanted, even with a chip on my shoulder thinking that I should already be smart enough to publish what I wanted no matter what.

In the end, it was my method—and my refusal to give up—that led me to exactly where I wished to be. Not long after finishing my manuscript and sending it to exactly the one place I could imagined it belonged, Derek wrote me back and told me he wanted to publish Ever; that he already had vision for exactly what kind of form that it could take, a perfect fit. I remember reading his response on my mom’s computer that afternoon feeling like I’d finally burst through my own seams, suddenly able to think of nothing else that I could do but run outside and jump in the pool in all my clothes. It had all felt so impossible until it didn’t, and now absolutely everything had changed. I could already hardly remember what it had felt like to feel so strange, so someone else, and though that sinking feeling would return on down the line as I went back to the drawing board each time for each new book, it would be in a different way, of a different aura—no longer arbitrary and insane, but fed by method and rapport.

When I talk to younger writers now, I often try to impart this lesson through the idea that if you want to publish a book, someday you will—though of course it’s easier to say once you’ve already felt it. Nevertheless, it remains true that thinking this way should be much more sustaining than the belief that you have to learn to jump through hoops to please the master, rather than the inverse, that the work comes first, and all the rest is window dressing. Sounds like bullshit, maybe, when in the pits, seeing what seems like so much networking and ego-baiting as necessary alongside the already steep grind of returning to the page day in day out without a prize—but also, in the end, without the struggle of creation and transmission combined, what would publishing even be? Anybody can write, but few are thick enough to want to until their eyes bleed, after all, and there’s a certain sort of nobility in learning to withstand the thrall for long enough to actually glimpse the reason you are here, wanting to do this. Like most great things, it’s more a process than a product, and in the end, all that’s really holding you back is your own fortitude for fear and loathing.

There’s something to be said, too, for starting somewhere, marking a line in the sand with your own hand, finally, even if it turns out to look not at all like what you’d expected. In some ways, publishing your first book becomes a sort of permission to realize you can make another, now newly armed with info you couldn’t have had previously, not only about the work, but about yourself. If nothing else, publishing gives you a ledge from which to jump, having been changed by the process that begat it from the start. I can say for sure that had I landed anywhere but Calamari, I’d probably be a much different person than I am—but does that mean that finding the right publisher served to change me? I don’t think so; it seems more so that what we’re meant to be is what we’ll be, and half the battle is not getting bucked off before you’ve learned anything. Rather than one foot in front of the other, a linear process earned from math, writing is often like being—it just keeps happening, and by the time you realize you’ve ended up anywhere, you’re already on your way to somewhere else.

I should suppose that’s enough for now. In these first six posts, I’ve mostly covered all the lead-up in exploration to how my path in publishing began. In Calamari Part 2, I’ll get into more here about the actual publication process for Ever, what I learned from working with Derek that first time, and how it informed my overall direction in the long run. Thanks for reading.

“…Anybody can write, but few are thick enough to want to until their eyes bleed…?”

Isn’t that the truth. Another dandy post Mr Butler.

love these. would be cool to see one about the background & influence of HTMLG as well