Mystery Bag - Ravn

On the passionate, disorienting, and necessarily piecemeal effects of Olga Ravn's novel-in-forms, My Work

I kind of cheated pulling the next read from my mystery bag, the thickest book left and therefore very easy to locate from in the blind. I already had it in my I wanted to read Olga Ravn’s My Work next (New Directions 2023, translated from the Danish by Sophia Hersi Smith and Jennifer Russell), based on having heard buzz about it, and having read and appreciated her first novel, The Employees, which did some interesting things with bending form and using voice to subtly expand the possibilities of science fiction. Despite the pleasure of not knowing what to read next, sometimes it feels more useful to follow one’s nose and let the reason for the interest come find you. You never know what taking something in will do to what you think you already understand; how minutely it can affect the way you see the world based on the nature it provides.

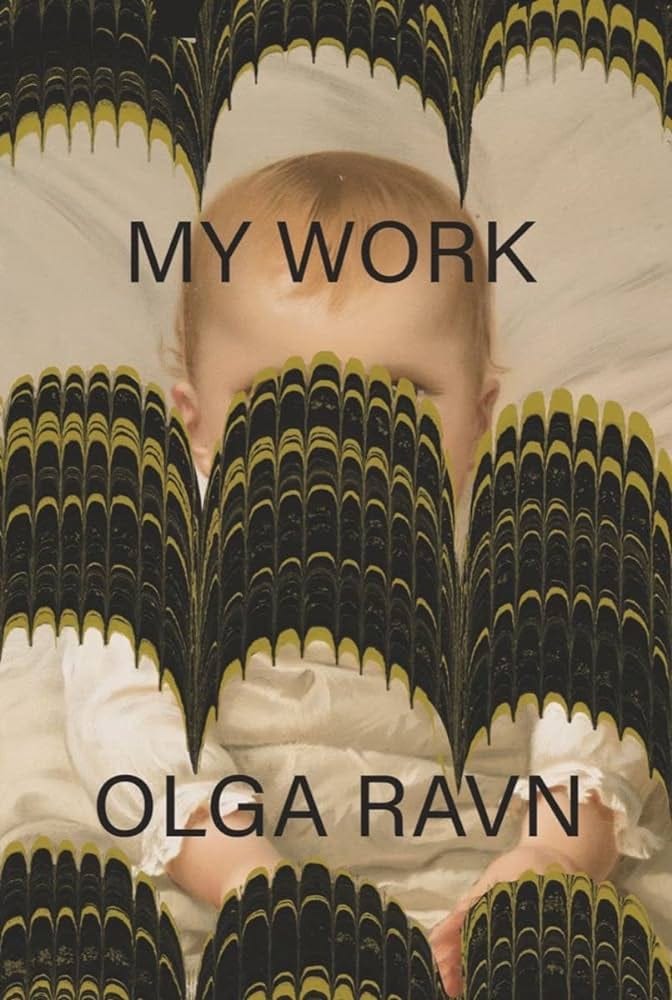

Though My Work is a novel, it very clearly takes no prisoners w/r/t its design. Flipping through its 391 pages, one finds a wide variety of forms forced to exist side by side—personal journal, stageplay, timesheet, free verse, prose miniature, letter, dialogue, index entry, lyrical fragment, essay, manifesto, pregnancy journal—all of it held together by irregular chapter headings that further demonstrate the effects of the narrator’s presence as authorial intermittency throughout: First Beginning, Second Beginning, Third Beginning... First Continuation, Second Continuation… Twenty-Seventh Continuation… First Ending, Second Ending…Ninth Ending. Ravn has made it clear she borrowed (her word, rather than ‘stolen’) the novel’s formal apparatus as a series of notebooks used by the protagonist, and the protagonist’s name, Anna, from Doris Lessing, utilizing the homage to strengthen My Work’s rather immediate valence within a specific lineage of women authors, including Shelley, Duras, Cusk, Boyer, Gilman, Walker, Woolf, Zürn. In particular, the question of how one writes—is able to write—given the long social and historical constraints governing the idea of women’s work both in the home and in the marketplace, particularly through the lens of becoming mother as an artist and sheer impossibility of creating space and time for one to have their own life alongside the responsibilities encroached upon them by their partners and their own bodies.

No surprise, then, that this book feels very, very angry—if in a way that has become uncertain of its own nature. From the very first line—“Who wrote this book?”—we can feel a specific sort of inert violence behind the page, one that seems to be attempting to bargain or think aloud with the reader (and the author) and itself to identify and hopefully harvest direction out of an anticipation of directionlessness. Anna is pregnant with her first child, partnered with a man, Aksel, who works full time and appears to have very immediate ideas about how he think his wife should handle their ‘shared’ experience of childbirth and childrearing. From very early on, Aksel comes off less as an ally and more as a stumbling block, always ready to question Anna’s practices and moods as if she owes him and the baby—and the world—a certain texture of behavior not becoming of her artistic temperament, and certainly not conducive to writing with any reliably regularity. Thus, the novel’s very structure, how it attempts to find footholds amid biological and social chaos, reflects and then embodies its own existential attempt to maintain flow, seeking personal sense amidst a form of ambient oppression so deeply ingrained in how things are that even to resist it marks one as insane, troubled, guilty.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Dividual to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.