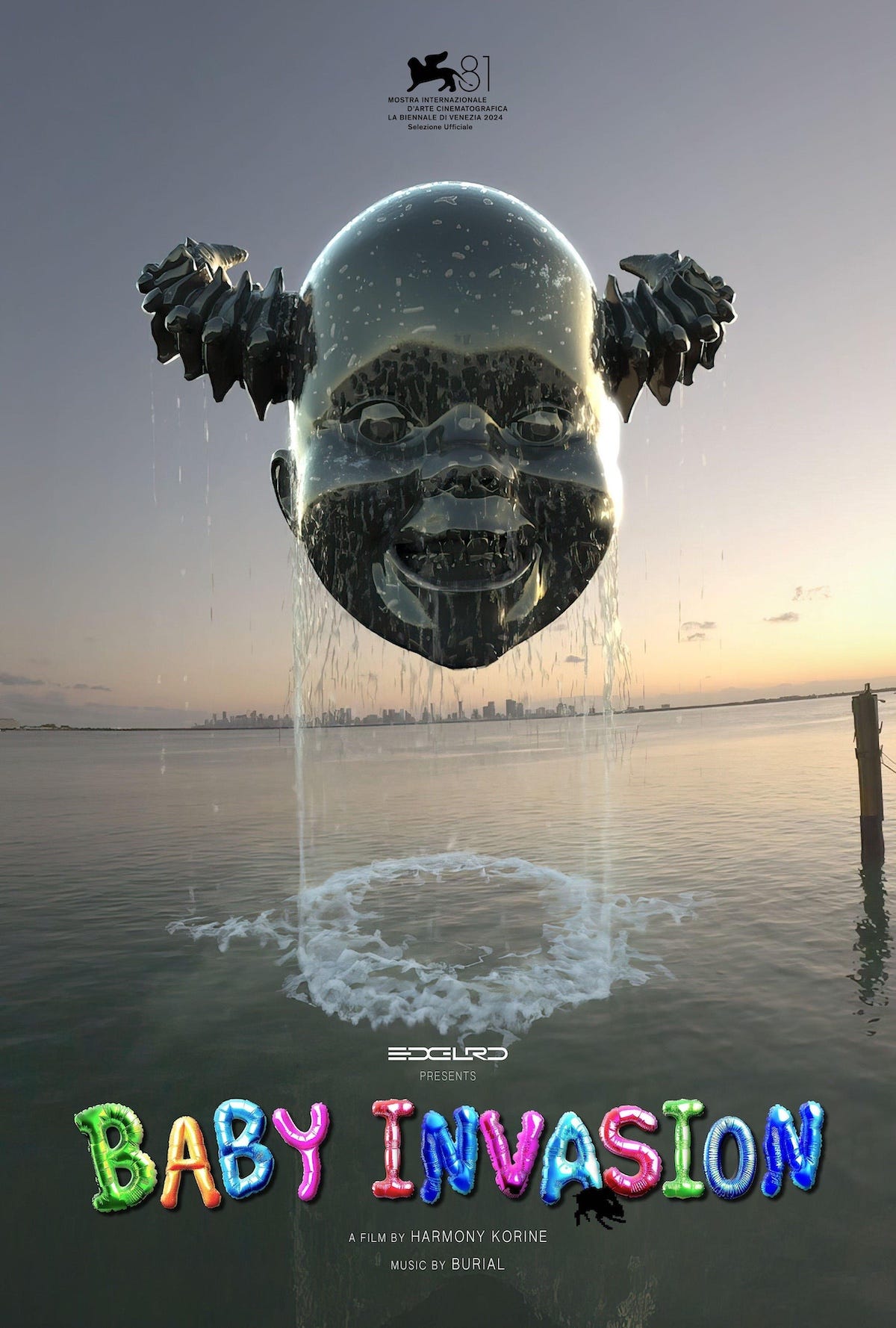

Harmony Korine's Baby Invasion

After a string of uncertainties, the latest creation from one of America's foremost avant-garde is among his best, and a true delight

It took me a while to get around to watching Baby Invasion. In younger years, I would have been chomping at the bit to consume any new Harmony Korine joint the first day it became available anywhere, but honestly it’s been a while since he flipped my wig—Trash Humpers (2009) being the last to really bring it. Mister Lonely (2007) was full of vibrant images but lacked the pizzazz of his earlier work; Spring Breakers (2012) I found tempting but ultimately reactionary and kind of uninspired; The Beach Bum (2019) was borderline corny and a little too full of try-hard, and at that point I started to believe that maybe Korine had used up all his swag. A disappointment but not a surprise, as it’s rare for avant garde artists who blow up young to maintain the same energy that brought them to the field in the first place. Success can make one weak if it dilutes the sauce that got you there in the beginning, and these days, most everybody with any commercial leaning at all gets beaten back into the shed eventually.

Thus, it was with a bit of a low bar that Baby Invasion (2024) came back around. Lately I’ve been finding myself more ready than ever to turn off boring entertainment the second it starts to feel pat, even if the pat comes from a place of trying to accomplish the opposite. So much media these days seems to be barely going through the motions, setting up a premise, however slant, and turning it to mush either by playing the same note over and over or bring on a ‘twist’ that is ultimately as predictable as the concept of a twist itself. If there’s anything I hate these days with TV media in particular, it’s the feeling of waiting for the show to be over so I can go back to being free, rather than feeling freed by the act of witness.

When trying to decide whether to rent or buy the stream, I insisted on rent, announcing that I doubted we’d be needing to watch Baby Invasion more than once even if it wasn’t a flop. Unlike his masterpieces—Gummo (1997), Julien Donkey-Boy (1999), and Trash Humpers (2009)—Korine’s most recent works had for me felt like a bit of a cauldron of memetic eyesores for eyesores’ sake, frontloading spectacle at any cost over the more immersive and obscure energy that made his work infinitely rewatchable.

All great artists change, of course, and we certainly can’t go back to early successes in hopes of seeing the same gesture repeated differently, but Korine in particular had established himself as one of the foremost provocateurs of the American avant garde, and so I imagine my lowered expectations of his future work felt like the kind of let down you don’t want to have to admit. It seemed, in fact, to be the mark of a death knell of American experimentalism in general—if he can’t do it, who will step up to fill the void?

On its promotional surface, Baby Invasion seemed to promise more of the recent same, having been filmed inside a video game and overflowing with online streamer energy that I imagined would feel so on the nose with the bloat of being online that I’d rather skip it. Right out of the gate, though, that premise earmarked a different conceptual ideology that I’d expected—the film begins with an interview with the Tagalog game designer who’d originally built the world of Baby Invasion based off a dream—of a group of thieves with cute baby faces who break into rich people’s houses and steal their shit. Her interview explains how before the game had been completed, it got leaked to the dark web and became the basis of innumerable modded versions, which then leaked into reality when people started actually performing the robberies IRL.

Very quickly, then, the energy of the premise went from masturbatory, and into an uncanny valley of blurred identity and performative violence—about as pressing a topic as one might imagine, given the current state of the world, and also one so frequently miscast that aesthetics in general have struggled to harness without dumbing it down. I still felt skeptical, however, when the film shifted into its actual landscape—a kind of GTA-styled POV where we follow a group of CGI baby-faced ops gearing up to go on a mission in their van, armed to the teeth. Despite the obvious gaffe of it all, the graphics of the game are so realistically rendered, so high end, that it felt hard at times to remember what was happening onscreen was all virtually based; that these weren’t really actors, but avatars. Their stillness, likewise, when not in action, was obviously code, miming humanistic qualities like NPCs between cut-scenes.

Rather than seeming dull for that reason, the effect, for me, was innervating, especially given the violence to come. Even while performing atrocious acts, assassinating civilians, or simply hanging out and enjoying the artificial horizon at the scene of the crime, the antagonists total lack of emotion or passion added a nasty layer of coldness to their behavior—the kind of sociopathy we tend to extend only to AI, but here so realistic it might as well be anybody’s neighbor—as so it is.

The film’s complete lack of spoken dialogue throughout reinforced this feeling to great effect. Some of the most excruciatingly boring shit being made these days—even in shows known as the opposite, such as The Pitt and Succession—comes from overly try-hard back and forth clearly meant to evoke melodrama rather than aesthetic quality. Without unnecessary dickering around about story arc and character development, I felt allowed to lay back and enjoy the ride, waiting to see what happens when the scenes can’t rely on language to do their job. Add to this the film’s heavily affective ambient score composed by Burial, and for once it felt like I was actually inside of something for once; not just being entertained or even screwed around with for art’s sake, but along for the ride.

The effect is hypnotizing—quite in a similar way to how I’ve taken in recent years to watching speedrun streamers before bed. Far from being merely unrealistic, the architecture of video games, which simulates reality through code, creates a space that in appending reality with the limitlessness of dreams, we’re allowed into the kind of liminal space that instances of uncanny valley IRL can only brush. As we follow the film’s extremely simple premise forward, then, we’re being drawn into a curiosity of energy that we as a culture continuously fetishize from a remove—a nexus between extreme brutality and the everyday—while being forced to feel at once both ends of the pole—the banality of evil, yes, but also the evil of banality, and what happens when two opposites collide. Rather than ever being boring or intentionally not-boring, then, the film takes on an elongated effect of living out the unknown from the safety of your chair.

In this way, Baby Invasion might be thought of as more of a work of literature than cinema; it stacks its sentences one by one to create blocks of exploration that compile inside the consumer’s mind. No matter who’s watching, you’ve simply never seen the sorts of images and workflows that are being strung together here anywhere else all in one place, hearkening back to some of Korine’s earliest expressions of the desire to put onscreen things that previously hadn’t had a place, much less a realm.

Korine, in attempting to describe his more recent aesthetics in an interview about the film, described the necessity of contemporary art to move away from storytelling entirely, given its hardship in the face of so much modern glut, in favor of creating experiences, not plots or objects. Put that way, it’s an easier path to reconsider the notion of creating art in a commercially driven culture; the world is simply too large, too full of conflicting energies and ideas, too fast to land on any fact without generating platitudes. Instead, Korine’s process, as a reaction to the times, is about building layers and letting them cook on their own, in so many words; coming to the work, both as a creator and consumer, not with a goal in mind, but with the same willingness to discover the world before your very eyes even as it continues to defy being controlled.

Without question, Baby Invasion as a film is so full of ideas and energies that you could watch it a thousand times and see something new with every repeat. Throughout the 80 minute runtime, I found myself having to choose particular elements to focus on from moment to moment, knowing I was missing other layers in favor of examining the infinite details of any scene. The video game-like narrative of home invasion is only the base layer, as it turns out, and what you are attracted to onscreen is a bit of a choice amidst the many dozens of other signals the film compiles. A Twitch-like chat stream overlays the bulk of the movie, supplying user feedback that echoes what’s happening onscreen amidst a slew of spam and non-sequiturs. Other partitions flood with web junk, video game status updates, typed live chat between characters, and a wide variety of deep dream animals, faces, and spaces. While certain avatars are busy rounding up victims, or exploring the setting for unique objects, or just enjoying the view, others might be playing first person shooters on their phone, or following rabbit holes hidden in the game’s structure, some of which link to another reality where three masks kids appear to be playing the game from outside it. Perhaps most surrealistically, a literal bunny as big as a house appears between cracks in the firmament and in the sky, embodying something like a god in a realm where absurdism is the norm, and cute is verboten.

The overall effect is a wonder to behold. It suspends the viewer in a state of open consciousness, taking it all in in a state of simultaneous awe, horror, and joy. Korine’s splashy comment that “iShowSpeed is the new Tarkovsky”—tendered at a press conference where he also told the moderator that the film industry as we know it is in its death throes and must move on—feels less coyly inflammatory and more literal as we spiral down infinite mirror-effected tunnels into backrooms style sets and weird landscapes that should seem to have nothing to do with the central plot. The movie somehow feels alive, like it might rip itself open and reveal how it connects to your own home—an effect Korine has also mentioned as an immediate goal for future films—rather than a decoy trying to make a comment on a half-truth about mediated reality and mass violence, though it does those too. Ultimately, there’s no one “truth” to be mined here—there are millions, and somehow they feel even more accessible in being literally virtualized than pretending to evoke literal philosophies. For once, the film is actually larger than life, and it invites you to explore it by reducing your desire to interpret metaphor or meaning on the fly to a grand guignol. It’s simultaneously ridiculous and on the nose, spastic and meditative, horrifying and exciting, full of images that feel all too familiar and ones culled from an alien world we should be so lucky to ever experience outside of aesthetics.

If it isn’t clear by now, I loved Baby Invasion, and any question about Korine’s ability to continue to revamp and defy convention from the ground up has been squashed. It also represents the burgeoning future of a world that—like it or not—will be influenced by AI and mass psychosis, which to the adventurous soul should represent a challenge, not a threat. To remain relevant, after all, was never guaranteed, and the genie cannot be put back in the bottle, nor should it. Instead, we should hope that artists look to the future with the kind of eye that would see it from outside it, inspiring the desire to inspire revelation even as the medium and media devours itself for all to see. Ingenuity is medicine, not nightmare fuel, and as far as America might yet have to go in manifesting difference against tame-brained mediocrity, Harmony Korine stands at the cutting edge smoking a Cohiba with his eyes on the prize.

The thing I realized recently about Korine's work (I think it was AGGRO DR1FT that sparked this) is that even when it's not great (I also really didn't care for The Beach Bum or Mister Lonely) it's always really compelling because his films always feel like an expression of the collective American id in some way that I don't think I've ever seen from anyone else, at least not in cinema.

I gotta rewatch this one again - I tried while I was dealing with the flu and I do think I tried "too hard" to focus on everything going on rather than focus on one element or "scroll" between them as I watched. Your write-up does perfectly capture the energy of it though and Harmony did succeed in what he was attempting to achieve with it