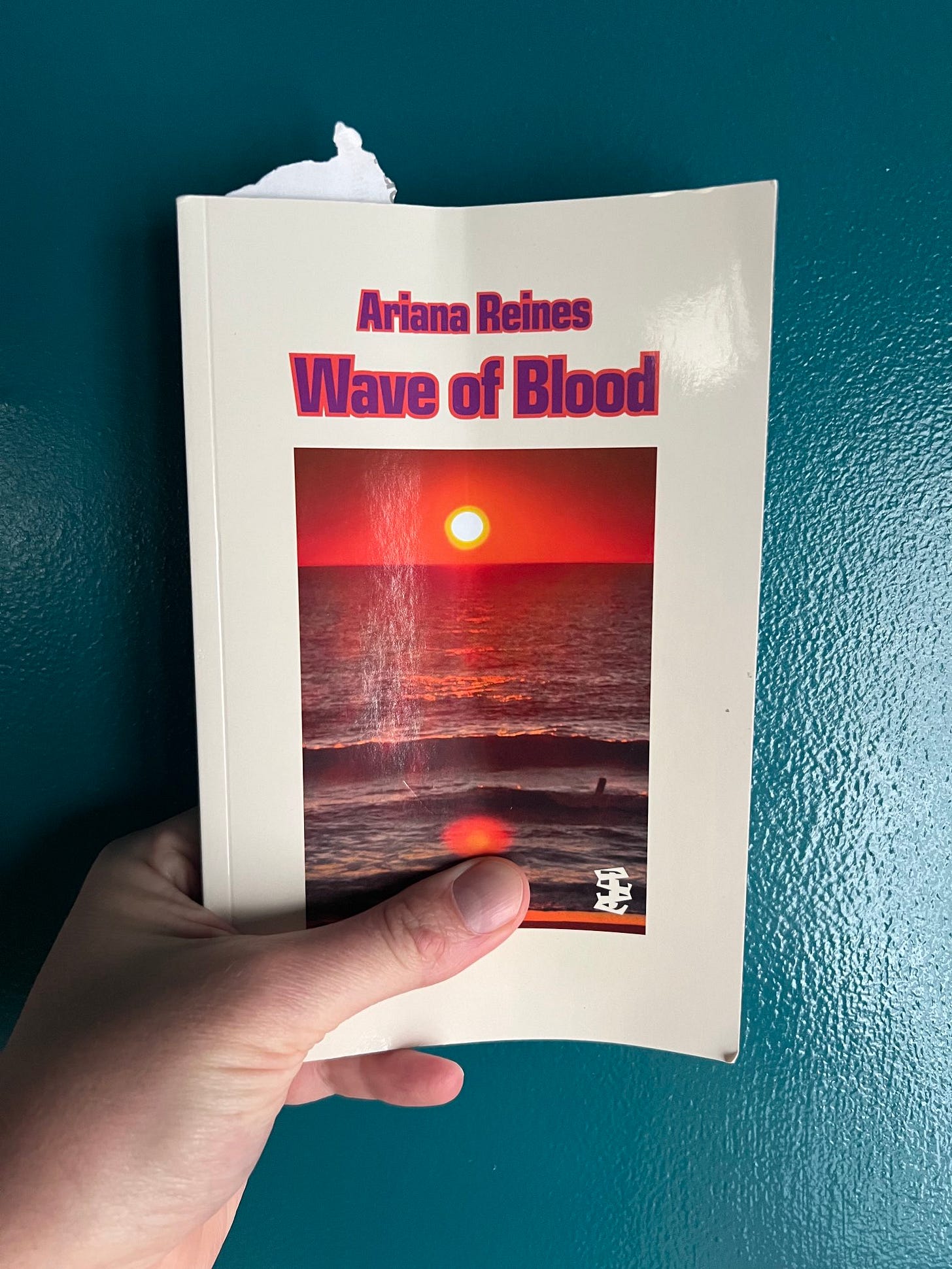

Ariana Reines's Wave of Blood

Another ambient, digressive review, this time focusing on one of my fav living poet's latest, a life-affirming, death-defying, and highly revealing hybrid text

Wave of Blood came out of nowhere to me. It used to seem easy to keep track of who is doing what when, and even with social media as prevalent as ever, things go missing. Some are never even heard of unless you know where to look.

This is, of course, in at least one way, a problem; especially as it conflicts with the idea that we are all immersively and continuous being made aware of everything thing that is the case.

I used to think if a tree fell in a forest and no one was there to hear it, it still did make a sound; in the last year or two, I’ve switched sides. I can’t remember if I’ve already pointed this out on this blog in the past, which is further proof of the mind being like a forest unto itself. Even when a tree does fall in the forest and someone is there to hear it, they might not; no?

Whatever the case, everything Ariana Reines publishes is a must-read. Wave of Blood arrived in my mailbox the day after I realized it exists. The copy I got looked like it had been folded width-wise down the middle, creasing it distinctly. The impression of that bending only extended past the cover for about 40 pages. Past that, there was no bend.

After reading the first four lines, I knew I would want to read the book cover to cover. Instead, I closed the book immediately and kept the feeling close to me until the next day.

I suppose it felt like a call to arms; even part of one I already feel in the midst of, in a daily struggle with my mind and work, and also with my world. I don’t mind the struggle entirely—in fact, I asked for it, without realizing what I was asking for.

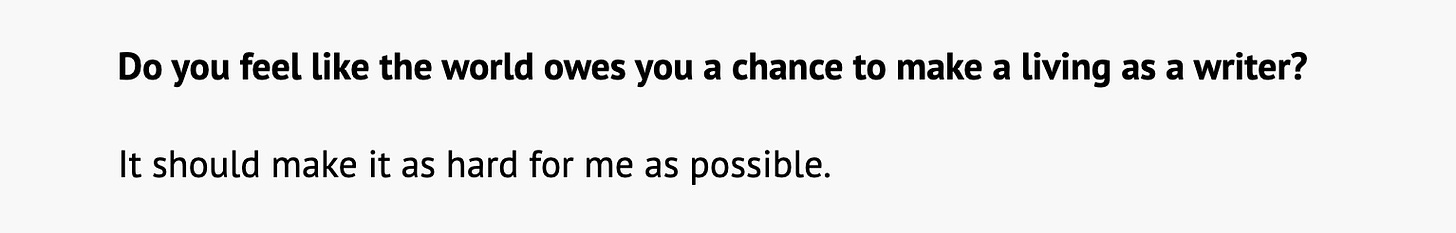

I find myself thinking (and laughing) a lot about an answer I semi-recently remembered I gave in March 2013 to Full Stop’s “questionnaire asking writers about the effect writing has had on their physical, emotional, and economic health; on the idea of poverty being a precondition for writing well; on what makes writing truthful to one’s self and to readers.”

Even a decade later, I can’t imagine a different answer, though I wish I could take it back the first time. Or do I?

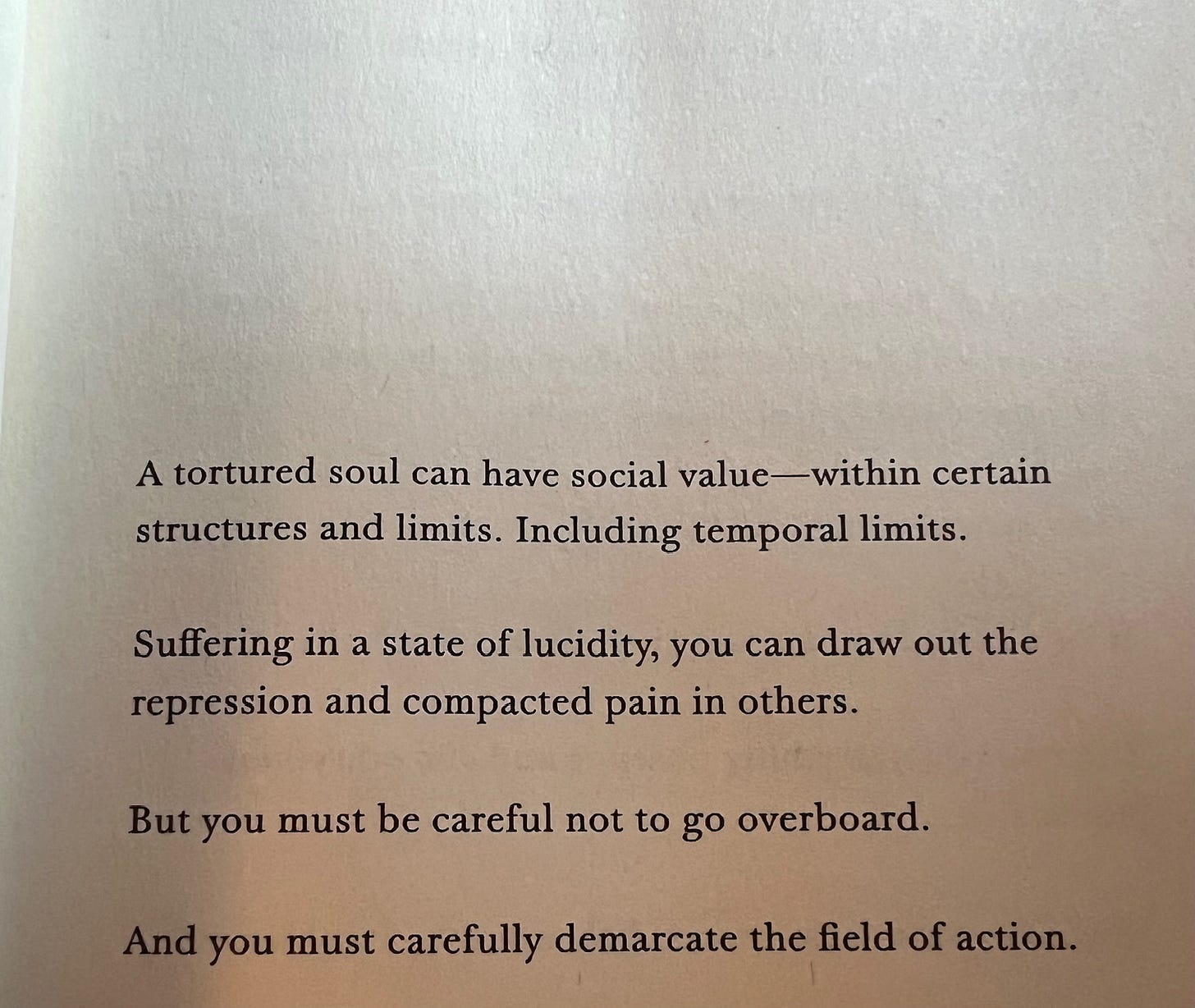

Wave of Blood faces the reader, as Reines has often done, with many of her cards on the table, and with other cards waiting to be dealt and revealed. Reading her is an experience as well as a performance; and unlike gazing into an abyss, gazing into someone else’s experience of the abyss provides a mean by which you might learn from their hardships and mistakes without having had to survive them yourself. At least not in the same way (which would be impossible), or not yet (which is yet to be known). One of the pleasure of her work in particular is how deftly she is able to inhabit the breadth of own life before your very eyes and come back speaking to you not as a willing sage, but as a guide who can’t go with you.

No one can go with you but your idea of God. Whether you believe one exists or not, it would be foolish to argue against God, but it hasn’t stopped me from trying.

Now, I am tired of trying. At the same time, I am more ready than I have ever been to face myself. I have only begun asking myself the kinds of questions that an unchallenged me would have baited then kicked down the road for later.

Returning to read the first page of Wave of Blood a second time, having held it in mind a while, it read the same; but I was different.

Everything that doesn’t kill us makes us different.

Like many great writers, Reines makes thinking and speaking aloud about yourself in relation to the horrors of the world appear much easier than it is. There’s a reason some of the most enchanting works of art produce the highest number of terrible imitators. I imagine her power comes from having exposed herself in ways that most who live never choose to.

Reines writes in Wave of Blood about her mother’s death, and how her mother’s struggle with mental illness and homelessness affected her life, in a way that brings me, in the same breath, horror and peace. Horror to understand in my own way that someone so powerful had to suffer in ways I can both imagine through my own struggles, and never imagine; peace to know that though we feel alone in ourselves at our lowest points, and how that aloneness may haunt us to madness, there are others who have also looked the wave of blood in the eye and not only survive, but decided to write about it.

In aloneness, you might imagine no one else is seeing what you’re seeing. Such logic quite easily can lead to no longer wanting to live. If there’s any goal a literature might wish to attain—short of successfully completing all of the texts that would someday line Borges’s Library of Babel—it might be lessening in anyone the feeling of no longer wanting to live.

Without an eye to read, there are no reason for books. Machines don’t need fiction, and thus will never be able to write it. The point, for us, should be to survive.

No one knows why. Sometimes it’s personal.

As a book, Wave of Blood flows freely. It is the kind of book with a lot of white space and breaks between lines, mixing texts that read like journals and lectures alongside more formal, titled poetry, making it easy to scan through, despite the intensity of the subject matter. As a Virgil, Reines is highly relatable and practical-seeming, delivering fluidly line-broken thoughts about her personal, spiritual, professional, romantic, and artistic life using a fragmented but intimate tone that reminds me now of standing on the precipice between realms. If you meet someone at the edge of two dimensions, for instance, you’re not likely going to be talking about who’s on first. Your memory of the world will hardly reflect what it held, but it will have been yours.

Wave of Blood looks to the future. Reines refers frequently to recent major political events, including Gaza, about which she is able to opine from personal experience without feeling preached at, despite the endless complexities of her family history. She lays plain both the horror of atrocity, admitting the difficulty of having to exist within an unending state of war, if “only” as a spectator, over time, while conceding that her views could be affected by her feelings and her past, from which an immensity of personal meaning is derived, one that can’t flipped like a switch. Like many great things, it has to be lived with in order to be imagined, and even in its imagination, understanding elides because it is too immense. Both for any person and for all of us.

In that way, Wave of Blood feels like an antidote to social media. Sharing a space that is too private and raw to be transmuted into art, and yet contains the same vitality that a work of art does in its attempt to capture any one or few of the many reflections a moment contains.

As a model, the text creates desire to see the same in others. It helps me imagine a means of sharing information that isn’t aggressively influenced and/or doctored by any source. Its immediacy and intimacy together courts revelation by for once standing up against the darkness without anyone needing to be in the same space to see you.

“We’re at a point in language as though we’ve become embarrassed by it,” Reines writes. “In so many ancient stories the world is created through language. And we also create our reality through what we speak. And so how much war-like self-animosity, loathing, loneliness, shittiness, insanity, are we also reproducing by our own embarrassment, and our own incapacity to use this gift of language with the kind of energy and commitment and love it deserves?”

It is one thing to wear a mask in front of others; it is another to wear a mask when alone. No one wants to wear a mask over a mask. Wearing enough masks, you eventually suffocate.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Dividual to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.