Annie Ernaux's A Woman's Story

Reflecting on the legendary French avant-garde memoirist's elucidation of her mother's Alzheimer's through my own, toward a means of unpacking the protective & destructive powers of language

I used to feel electric when I sat down at my computer to write. I knew how to leave the world behind me and not look back. As if all language were a black hole, beyond the edge of which nothing much else mattered but the experience of being immersed, one word at a time. As if all I had to do to disappear was open up.

A couple years ago, at a point in my life in which everything I was had come unbound, a friend referred to my description of working in this way as “writing without armor,” suggesting that I might arm myself before I dive into the abyss—to protect myself from…well, myself. Actually, I’m still trying to figure out what I should be protecting myself from, and what it means—a consideration that recently, in the wake of the coming unbound, trying to return from it, feels more vital to not only survival, but to my willingness to want to, than I would have liked to admit. Why isn’t the work itself my protection, I must have wondered? What could really hurt me when all writing is, as others have described it, is a series of choices? Couldn’t I trust myself to choose? Or if not, clearly, weren’t those choices part of the reason I’m alive? Isn’t it my ability to make mistakes, to go where I do not know, that simultaneously opens the possibility of wonder and of harm? Isn’t knowing that no one ever could be given a series of choices as numerous and continuous as is required in the writing of any single sentence and choose correctly every time the exact reason I—a fool, a gambler, a lightning rod for my own mind—wanted to write?

Of course, we know there is no guide by which to measure whether the correct choice has been chosen when selecting the next word, despite how nice certain words feel when placed together. There is what’s familiar and what’s adjacent to that, then there’s words that simply seem to make no sense. Corrosion comes to mind wanting to begin this next sentence; exactly the kind of frame that could describe the mass of pet words I’ve gotten used to turning toward almost unconsciously, as if expecting the floor to fall out from underneath my feet before I get the chance to say what I have come to say. As if it isn’t me who chooses the words at all, but my life. What is the difference between me and my life, then? What about you and yours? What about absolutely every single one of every person you’ve ever seen, each continuously finding ourselves at the front and center of the path we think we’re on, no matter how unnamable and unrelatable, ours and not ours, all at once?

When I try to remember how I got caught here in how I am, why what comes first for me is words that often express discomfort, uncertainty, and often pain, I think of my mother; as a counterbalance, rather than a guidepost. It was my mother, after all, who taught me to love reading, to believe enough in myself that I could feel free enough to chase my imagination onto paper and think that I have anything to say. Recently, I found a copy of a pay-to-play poetry anthology that technically serves as my first true publication, as a 17-year-old, which housed two “poems” I had mailed in along with a check for a copy of the book: an obviously embarrassing, sentimental stab at a love poem, mostly mimicking the alt-rock lyrics I cleaved onto throughout high school. A handwritten note from Mom stuck between the pages describes her surprise at witnessing my maturing depth of feeling from afar and offers kind encouragement over my aspiration to share it, to be vulnerable. Despite our family feeling “normal,” as in well-stocked, wholesome in spirit, and often “safe,” we weren’t the kind like others that said “I love you” at every coming or going; physical affection was there but not as free as it was in other households, which seemed more open; and I certainly refused to share even a whiff of my own romances, refusing to say so when I had a date, much less real feelings. As an adult, I can see the sweet way my mother talks around or past the fact that the poems suck, being my mother, alluding already to the future; what, if I choose, might someday come, both in love, and in ambition. What the poems actually say isn’t what mattered, by that measure; what mattered, if anything, is the memory, without which I might be somewhere else than where I am, having disappeared out of the life I have now, using different language, another world. Or maybe I’d still be exactly right here, but typing about some other way the world had changed me without my knowing in the moment.

For years thereafter, my mother read as much of my work as I would let her, always asking for copies of journals where I’d publish, or copies of my drafts. Closer to the end, once her Alzheimer’s started eating through her mind, she might ask me five times during lunch what I was working on next, and if I had a title. Sometimes I’d tell her, quite precisely, and other times I’d mumble into my hands or make something up, not wanting to let her in too early, if at all. I remember a sense of victory when, upon the release of my fourth novel, Three Hundred Million, she read the first few pages and admitted she didn’t think she could read this one; that it was too much. Yes, I thought, thumbing the unread book’s edge, finally; I’ve won. This one was mine; it contained information that even the one person who loved me in a way no one else ever could preferred not to have to bear, which proved to me at last that who I was could not be contained by who I’d been.

Even then, though, I don’t really think I believed this; that I took pleasure in finally creating something that would make my mother turn her head. There was and still is a writhing part of me that refuses to accept the limit of needing to learn not to stick my hand in the fire, to not be burned. It is the same part of me that learned not to want to sleep from very young, both due to nightmares and night terrors, which had been there with me since before I remember anything else, and from a developing sense of need for vigilance; that I was aware of there being unseen forces in the world that no one seemed to comment on or could explain away with facts. Even as an infant, I didn’t want to be consoled, as my mother describes in my baby journal, explaining how I’d scream even more if she tried to come near, leaving her no choice but to either violate that or wait it out. Imagining her horror, on the far side of that memory, seeing the child she’d brought into the world unable to recognize her due to the incarnations in his brain, evokes the texture of the nature of a kind of horror that cannot be contained by words. Publishing a book my mother refused to read, finally, proved that there was a limit to the navigable nature of even our most sacred understandings; that there were choices one could make that could change the ground beneath our feet, even in the places we’d thought impregnable, permissionless. As if pain alone could make a man. As if we should worship our misgivings for what they provide by way of recognizing how we are and how we’re not.

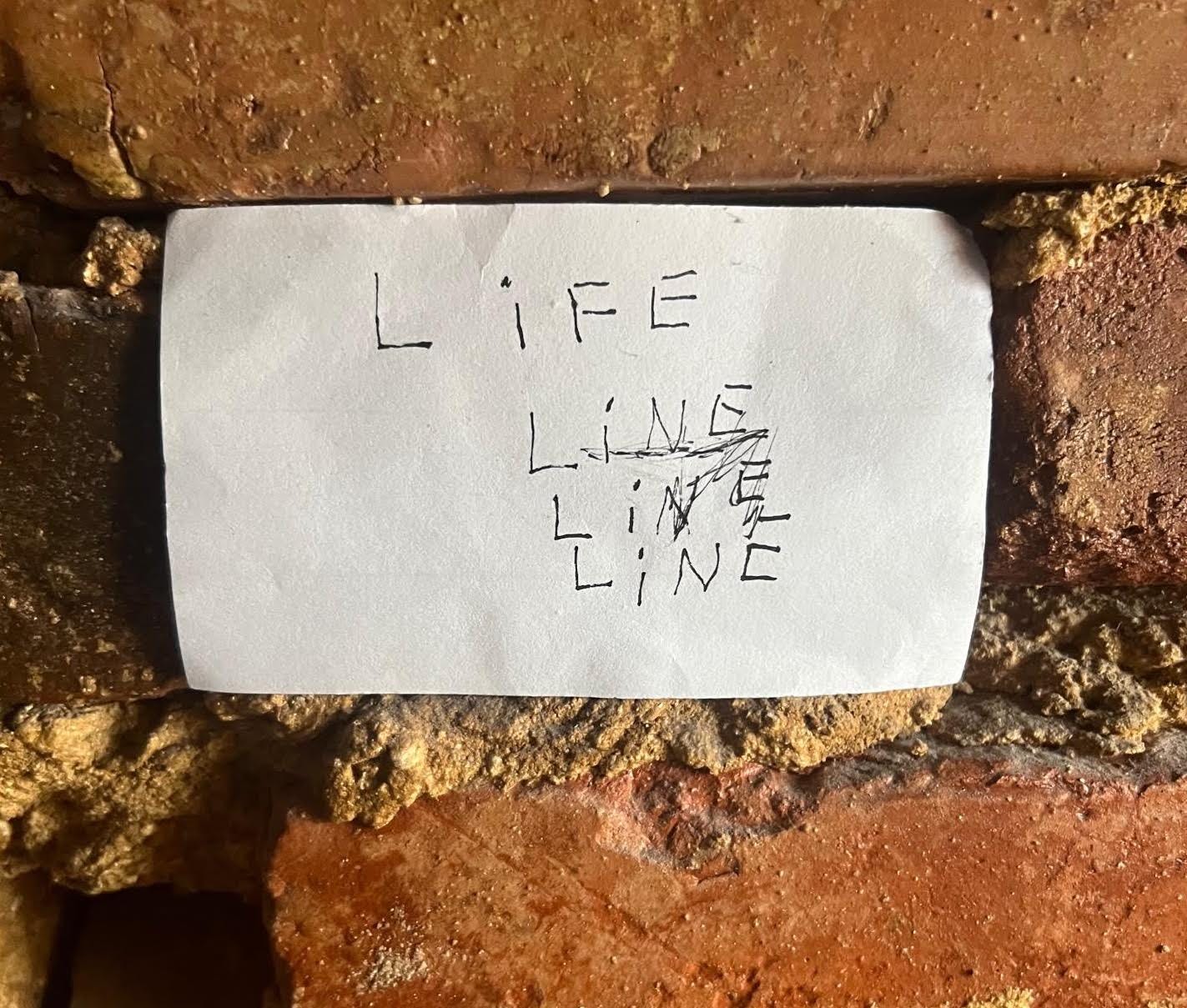

In my office, fixed to the brick wall behind my head, I have an index card marked by my mom’s hand during the later years of her disease. LiFE, the top line reads, the crooked letters and lowercase i amidst all caps resembling a child’s script, as her motor skills devolved. Then, offset in an indented column:

LiNE

LiNE

LiNE

—the three iterations of the final word each embattled—some parts partly underlined, or traced over double, turning to scribble at a letter’s hinge—as if she were trying to really get it right, almost a mantra. Throughout my life, small notes like this littered our house, as reminders or to-do lists left out on the counter, mostly by mom but also by us others following her lead—the kind of stuff these days you’d just send a text about or schedule a calendar reminder for. In the process of emptying her house after her death, I scavenged hundreds of notes like these, as mementos of the minutiae of her days, as well as evidence of how her mind changed with her illness, shifting from the swooping, beautifully illegible cursive found in her journals to the elemental fragments and gibberish of her late years. For now, I can still remember why she’d written this particular string of words on this particular note card—she’d wanted to remember to remind me to buy her a Lifeline bracelet, so she’d have help if she fell, as after my father’s death, after caring for him through the eight years of his own Alzheimer’s, she lived alone. She didn’t understand that the nice man who came over every day was her caregiver; that if she fell, someone was there. Up to the end, she maintained belief in her ability to recognize whether she was in control of her own mind, telling the doctor her diagnosed her for the first time with dementia, that if anyone should know how her own mind felt, it was her, especially having seen the effects of the disease in excruciating detail as it befell her husband of forty years. She didn’t need the Lifeline system, and yet she wanted one, especially after seeing ads for it on the TV, or hearing people who didn’t live nearby saying she should have one, based on her uncertain, and eventually unreliable, reports on her own experience of life. Her life had abandoned her without her knowing, as it stood; she could no longer be expected to gauge her own best interests, much less to make a choice, to take a stand.

Learning to give up trying to explain this to her, to in fact need to work against her, to keep secrets, so as to protect her from herself, I realize now had been the tipping point in my own ability to gauge my own limits. Her illness, back-to-back with the end of my father’s illness, which each were very different despite carrying the same label, eventually begat a mode in me that would lay waste to attitudes and attributes I’d gotten so used to relying on that even as they disappeared I refused to negotiate, much less to turn back. If even my mother’s memory of herself, and then of me, could be unclasped, what good was protecting anything? What was a lifeline really, but another fleeting mark drawn in cold sand, requiring a monthly payment and reliance on a corporation for the most important work a loving child might be forced to withstand, if they will, both in their will and in their own most brittle memories?

Either way, no matter how you choose to spell it out, my mother died—of an undetected ovarian cancer, not Alzheimer’s, on the record, though without question had she began able to speak up better, or had the doctors bothered to listen to her when she spoke, there could have been a chance to catch it early extend life—and in the process suffered disgraces that no armor could defend—at the hands of friends and family, afraid of their own inability to relate to her from within illness as well as from the continuous torture of living at the center of a vortex that only at times resembles anything you’d spent your life calling your life. And worst of all, so as I felt it, the surrounding world continued on. No moment of silence or life of mourning could counteract even a second of what went missing in her last breath, to be felt by me and me alone, remembered as only I could, until I couldn’t. Those are the facts. No way to go back and alter or undo the moments and memories that I can see more clearly now as what they are, from finally far enough ahead that I can’t change them, though they still change me—right there most every second, waiting to surface from the deluge of other facts held as hostage in my head, sometimes tender, sometimes more capable of damage than they had been from the start. After a while, yes, without armor, the continuous deluge becomes a blur, a broken wall inside a labyrinth full of broken walls, as with an erased map of a prior version of the same landscape you’ve been wandering around all of this time, thinking you know what you know sometimes, and sometimes knowing more than ever that you could never.

Unlike my mother, I preferred to write my notes to self on the backs of my hands. I liked having my flesh as a desk I carried with me; how it looked like shapeshifting tattoos, a little mess; how the blue or black ink would sometimes smear and blur, losing the meaning of the message to begin with. Mostly any note I made I already knew I wouldn’t need, able to remember it without the prod, but also feeling somehow safer without needing to rely on that alone. Similarly, I kept a pad and pen beside my bed at night so I could write down things I dreamed of or imagined from the cusp, different from day notes solely in that without the record they’d disappear, as most dreams must. My handwriting remained sloppy either way, conscious or half-conscious, most effective, in my mind, when rendered quickly and without custom, so as to preserve their energy over their will. I liked more when I couldn’t decipher what I’d written in my sleep than when I could tell exactly what I meant, leaving room for interpretation, boxing out utility in favor of texture; a sign of something I might not know I knew. I’d learned from my dad to sign my name by making chaotic scribbles, different every time. I remember standing in checkout lines at stores while the cashier would call the manager since the payee’s signature and the back of his ID failed to match; how I’d both feel tickled and excited to see him angry, insisting he was really who he claimed to be: himself.

Later, in the more advanced stages of his illness, he’d shift to scribbling madly all the time, no sense intact. He’d draw crooked, looping lines across the margins of any book that he could find, tearing the pages from the spine in bunches only after he’d doctored them up to the liking of whatever in him drew him to draw, having hardly read a book or made a drawing ever really in his life before he lost grip on the grip that held him back. No matter what he drew or read, or what he wanted or I wanted, his story ended, left now nowhere but in the heads and hands of those, like me, who had been there when it went down. He is alive, still, in the sense that death alone could not remove him from the world; that, known or not, his influence continues to influence its own traction in his absence from everything he left behind, including me, including now.

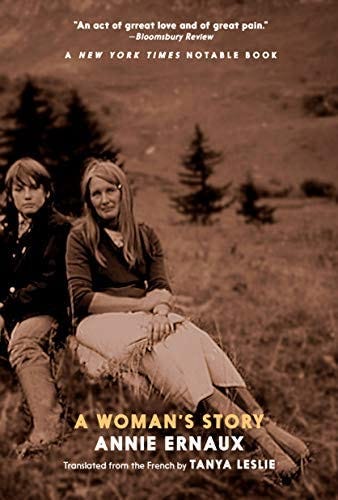

I began this writing in an attempt to talk my way into talking about Annie Ernaux; in particular, A Woman’s Story, which she describes, near the end of the book, as her attempt to “find the words that will reunite the demented woman she had become with the strong, radiant woman she once was.” Later in the evening after having written what I’ve written above, without touching base at all with the actual content of the memoir, another friend brought up Ernaux in the context of not wanting to let the caricature of readers’ expectations influence her writing, underlining how writing itself both as a practice and experience is alive, and should be allowed to go wherever it needs to, no matter what the forum calls for—that in the blur is where locate anything resembling our own truth. My friend also mentioned an essay she loved, where the author had set up to interview an artist and instead found themselves writing about their mother, leaving his intentions for the essay in the dust. “Actually, it’s not as good as I thought it was,” my friend commented after texting me a link, laughing. How did exactly this happen, I thought, and why does what I’m working on always find these small, strange ways of relocating into my reality? Or maybe more: how can I wear armor if I don’t know when and where and how and what I’m fighting? Shouldn’t I cut all of the words above from here and start again? What does where I am have to do with where I meant to go?

A Woman’s Story begins—seventy pages before the revelation of the above-quoted reason for the project of the book—with a 26-word compound sentence, initiated by three words she refers to again later in the book as words she had to overcome the fear of to be able to put down onto paper: “My mother died.” Everybody knows what these words mean, in theory; but from inside them, no one really knows, no matter how they think they might, what they might do. Nine pages later, Ernaux explains it took three weeks after her funeral before the language came, “Not as the first line of a letter but as the opening of a book.” Three weeks, before the fact of the death, with all its fear in leading up, could be framed into a mechanism of narration that might inscribe it, for the author, into the world, not just for her, but for any other who might someday, now or later, come to read.

Despite the universality of grief, the supposed knowing we call carry that not only are we going to die but all of those we love the most must also, there is an unspeakableness that underlies it, its shape akin only to the concurrent understanding of how no matter what we mean to say, words often fail. Instead we’re forced to rely, if we must communicate at all, on the empathy of others to be able to source the illicit meaning of the feelings that undergird experiences we both understand conceptually and yet cannot simulate outside ourself; and, likewise, the resulting anxiety of influence within that, in wanting to be heard and seen, to locate even a shred of understanding within the vortex of mourning, which carries on both with you and without you, and never really fully fades, only becomes something you can live with as bit by bit you learn to renegotiate the terms by which you interact with your own existence, while simultaneously nearly physiologically unable to separate your expectations and intentions from the isolating connotations of a world-shattering experience of pain.

“Perhaps I should wait until her illness and death have merged into the past,” Ernaux wonders aloud, on the page, “like other events in my life—my father’s death and the breakup with my husband—so that I feel the detachment which makes it easier to analyze one’s memories. But right now I am incapable of doing anything else.” Incapable of doing anything else. Sounds like hyperbole, doesn’t it, or at least we’re supposed to want to think it is. Surely we should be able to imagine Ernaux going about the rest of her life outside the writing: eating, bathing, sleeping, whatever else. Most people shouldn’t want to have to imagine a situation they’ve become reduced to a shell of themselves, by way of living their own life, making their own choices, stuck like a link in a chain, unwilling or unable to continue to take part in the world we seem to share with them, always at a distance no matter how close, even when touching. The abstract gap that manifests itself from out of unasked change—suffused for some by God or other faith—comes part and parcel with the silence that arrives alongside it, installing unseen architecture that each must learn to renegotiate all on their own, like learning to live inside another body on a dime, if still known under the same name, girded by experiences and memories that by turns feel impossible to make compatible and soaked in the essence of a way you really are and can’t quite see. Now walk this line. Now do whatever else you want with your time before it’s up. Now try to sleep.

Now it appears as if I’m the one speaking hyperbole, in being tugged again to try to underline an apparition in a grid. I see the words come out of me, onto the screen, and I can read them, even narrate them, stacking up footnotes in my mind for every phrase and shift of tone where I might have found a way to be more specific, and even more specific, slowly walling myself in. Lately, I’ve found myself trailing off in midst of reading, needing to go back and read the same lines many times before it sticks enough to carry on. Then the paragraph the sentence fits inside needs to be reread, for its context, and probably often the page, too, to be sure. Even then, often still nothing sticks, and reading begins to feel more like laying layers of paint onto a wall, the actual words placed on the page still under there somewhere, unchanged from what they’d been but in my mind.

Of course, any aesthetic experience leaves something wanting, no matter how effectively it charts its course through its unknown. It seems foolish to want to point to now and say it’s more impossible than it has ever been to glean a meaning from in the sprawl, but if there’s anything that serves as ballast for the loss of intimacy in much contemporary work, I’d say it comes from the insistence of the manufacture of utility, even of purposefulness, that quickly becomes the apparent bottom line in any shared experience of—I want here to say media, but instead I’ll use the dirty word—art. In a space that moves so fast that even viral hits have all the staying power of a dart, where can the idea of meaning, if never meaning itself, hold fast, take shape? Without an ideologically coherent basis, whose experience can play the role not of a balm, but of a record, in which the noise no longer fully inundates the signal to the point that no one could want, or bear, to continue walking on beside?

It feels funny finding myself talking over Ernaux now, in a way, trying to find my own beat in the long line of people willing, if not quite ready or able, to stand up at the front side of their own time. Another synchronicity, it seems, in having come across her work during a time where suddenly the idea of armor feels not like a capitulation, but a way to wander even deeper in. A world of fire burns up whatever is put into it, of course, and there is something to be learned from getting skunked, but there is also more there, underneath the layers that would defunct the unstudied surveyor, which if I’m being honest seems the primary reason for the lack I feel in wanting to see others try and fail; to see what kind of smoke comes off their burning, and what might be learned from how our lifelines cross in the language that we share. “I am the only archivist,” Ernaux explains, in trying to explain the feeling of suddenly finding one’s self at the tip of the sword bore by the generations of mothers and daughters that came before her; feeling the weight of that, waiting for it to somehow settle in her into fingers, to find the right words to type to bump into truth. Writing, then, seems to be a vessel, rather than the thing carried by the vessel. Like throwing wet spaghetti at a wall versus throwing the brittle sticks that come before they’re boiled. Or like the people taking pictures of the people taking pictures of the people taking pictures of the Mona Lisa without bothering to stop and look at the Mona Lisa. As if the Mona Lisa were as amazing of a painting as the hubbub surrounding it should suggest.

I’ve wondered often why Ernaux’s method of writing memoir feels more electric and alive than other memoirists, and how she’s able to pack so much power into such tight pages. Partly it’s her ability to consider her memory and time, in looking back, through an array; as certainly what we think of who we are and how we live, much less those all around us, is no more static than the memory itself. The unspoken friction of gaining gravity and traction around the traumas and the glories that mark the low and high points of our laugh creates a sort of landscape we may return to the way we would a city we’d once lived, finding it remade both by the lives of those within it as much or even more than our own shapeshifting path, with little choice but to reflect. What brings us pain does surely make us who we are, sure, but that in no way qualifies the experience of pain as something we know how to iterate or understand, to the extent that we even remember it how it happened, or if we remember it at all. Memory, like reality, is never static; could be described a thousand ways from a thousand moments, and yet there is a yearning in us to tell it right, right now, today.

By the same turn, the narrative persists throughout each fragment, which is perhaps why grief itself is so exhausting—it appears not as a single massive wave, but as a multitude of minor ones, lapping at you in nexuses and spaces that you both can and can’t see coming, as it is. Maybe Ernaux’s sublimeness comes from her ability to source feeling and meaning without the need of provocation toward resolution or redemption, while also continuous establishing points of references, windows in, where we may gather whiffs of sense from in the fray. There is a certain form of faith here, despite and/or perhaps in light of the impossibility of saying anything, that we, being those who choose to share it, as best we can, through language, image, at least have a chance to understand; that something unspeakable can be sensed, sat with, if never fully felt; rendered, if not recovered. We feel the potential of the power in our hands, to finally type the thing we mean to really say, which somehow against all hope we seem to still believe in enough to want to share; and we also feel the absence that underlines that, in wishing there were some better way, to not have failed; or to have failed “better,” to borrow Beckett’s now far-too-tidily employed catchphrase, which to him was only one of many lines.

“In actual fact, I spend a lot of time reflecting on what I have to say and on the choice and sequence of the words,” Ernaux relates about the early weeks of writing AWS from there inside it, “as if there existed only one immutable order which would convey the truth about my mother (although what this truth involves I am unable to say). When I am writing, the only thing matters to me is to find that particular order.” This explanation reveals an interesting conundrum, in knowing clearly that there is no single way to say it all; that really, whether writing about your mother’s death or today’s trip to the grocery, you could never fully capture the experience of an hour, much less months, years, lifetimes; and yet, the book is the book, and what exists inside the book, upon its publication, has been selected, placed on paper, given a body in thousands of copies, to be subjected to the eyes of everybody else who has no means to know you but by your word and what they discover in the experience of reading. It can never be enough, and it’s your only chance, and sometimes it doesn’t seem to matter either way at all, and sometimes it’s all that seems to matter, and then it’s spring, and then it’s fall, and then it’s spring again. Your mother is alive until she’s not, the same as you and everybody that you know. Eventually, after enough death, the words are all there is, within the memory of Earth, all aspect of whatever your beliefs are about what comes after death left notwithstanding on the record but among those who’ve passed on too. The rest remains to be seen, if not described.

“This book can be seen as a literary venture,” Ernaux writes—in trying, as she does often and so well, to explore aloud inside the book how it might be, which is also maybe what makes her writing so relatable, so real—“as its purpose is to find out the truth about my mother, a truth that can be conveyed only by words. (Neither photographs, nor my own memories, nor even the reminiscences of my family can bring me this truth.) And yet, in a sense, I would like to remain a cut below literature.” A cut below literature, I find myself repeating, over and over, to myself—itself a cut, placed into the face, inside my mind, of the conceit of literature itself, in how it suggests that in order to go anywhere, we first must close the doors on the idea that there’s a hallway we must walk, a map we must learn to use to negotiate the maze that manifests from out of passage through an attempt at reexperiencing one’s self at a remove. Easy to attach that, then, to another assault on the canon, on the contemporary desperation we’re forced to face in submitting ourselves to institutions for publication, to the absence of a gravity by which to fall and ever land again on solid ground. I feel sick of feeling the need to spit at so much of what I see as a stand-in for aesthetic experience whose aims are actually only glory, some whiff of fame that can be used to waft down on those who haven’t pulled themselves up on rungs of sales, tacky bits of commercial phrase that somehow authenticate to them their own experience through the timely lens of comprehension and cohesion, blah blah blah. All you end up sounding like is bitter, right? And who buys bitter but the bitter? Who hates the hater more than the hater hates himself?

So many masks, so little time. All the stuff we do between the typing of the words, erased from the record because there’s no real way to make it fit, which is why “literature” itself, as an institution we can mock, becomes its own joke, and why Ernaux’s approach here, as all throughout her work, feels so exciting; true in a way that others’ excess angling fails to broach. A Woman’s Story is as thin by width as a memoir gets, after all, contending by its own sense of compression that its supposed inadequacy should be a feature, not a bug; it lets you in, then it shuttles you around, and then it dumps you out, lets you decide. The narrative trajectory, while highly multivalent in AWS, is very simple: there is the death, and then the funeral, and then Ernaux’s desire, from within mourning, to connect the version of her mother amidst Alzheimer’s to who she was before the illness erased, stroke by stroke by stroke, her working mind, and so herself. The middle bulk of the book, buttressed by experiences of loss, traces her lineage the way one might for a private family journal, providing stark biographical details of childhood, early daily life, marriage, and work, touching on economy and custom as well as landmark moments of their family; much of it easily relatable as a portrait of a place and time as well as a person, which Ernaux interweaves, by intuition, the more elusive, interpretative snippets that give her mother’s person meaning amidst the facts: her mother’s laugh, her tendencies and habits, her eating habits and demeanor, her desire and word choices, bit by bit. Amongst that, too, Ernaux’s own experience of her mother as a mother girds the space with bolts of context for their relationship as mother and daughter, where they came together and where they split. Ernaux herself, as the authorial presence seeking station in the absence of the comfort of a mother’s presence in the world, appears in fits and peeks, often relying on the experience of the writing more than of the reality to guide her forward through the maze, without which we’d be lost, having no yard stick to gauge the range of feelings underneath. Very quickly, then, almost as quickly as life itself, we’re at the end, witnessing the moments where her mother’s illness began writing itself in over all those facts, taking what had once been familiar, even for granted, and replacing it with senility, dementia, within which Ernaux finds herself having, in a way, switched places with parent, and thereby losing the strand of who her mother even was despite all else. The facts are fractal; the way they are assembled and assessed brings them to life. It is a different kind of life than what we live with; it speaks without us, using our energy in hopes of making something, finally, that might withstand. It both knows us better than we know ourselves and knows nothing at all, except by proxy, thank God, and like God, of what it is to have survived them. In this way, maybe, the armor is as much the story as the story is, or even more; just as the sprawl of memories that come pouring out of me, at times, when I try to think of, about, and around what I am reading is the story, too, shared in tandem, and without direction, with every other reader of the same. The book is a site, then, different always for its creator than its host, a grave where we live on because there’s nowhere else; or because it is the where in nowhere, the yes in now.

I guess it’s because I read a slew of them both at the same time during this past summer that I find myself thinking of Hervé Guibert; particularly where in his memoir about living and dying with AIDS in the 1980s, in a quote that I can’t find now, he speaks of not being able to speak to others without speaking about his illness, and therefore choosing not to speak to anyone at all. “Yes, I can write it, and that’s undoubtedly what my madness is,” he writes near the book’s end. “I care more for my book than for my life, I won’t give up my book to save my life, and that’s what’s going to be the most difficult thing to make people believe and understand.” Anyone that’s written almost anything could understand that, so they think, as they think about it in their own way, and using means they’ve learned to try to simulate the thoughts of others in the same. But really, they don’t, they can’t, they shouldn’t want to. The experience of Other isn’t meant to be a stand-in for one’s own; if it were, literature would finally become the actual psychic weapon it seems to wish it could be. The trick about wanting to live forever is that you can’t imagine how it’d feel, and thereby can’t realize almost anything about it, besides the way it seems to seal us in our fate for even trying.

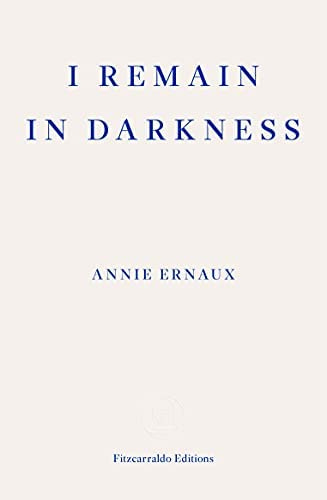

In that light, A Woman’s Story (1988 from Gallimard; 1991 tr. Tanya Leslie) makes an interesting pair with the first Ernaux book I read, I Remain in Darkness (1997 from Gallimard; 1999 tr. Tanya Leslie), which also chronicles the author’s experience of her mother’s Alzheimer’s, but in a very different form—essentially a journal, indexed by year and day into clumps of fragmentary notes and observations during the late stages of the illness, which Ernaux “delivers” (her word) in their original, raw form. In its narrow introduction, Ernaux describes having tried to write about her mother’s life while she was still alive, eventually destroying it, and, after her death, shifting instead to writing AWS. She’d felt unable to look at the notes she’d taken during the illness, she submits, and thus we understand the way the narrative of AWS is built outside the facts, in a way, having already experienced the end. In this way, IRID feels like a hidden labyrinth laid underneath the larger story, allowing tiny windows of reality through which we may peek to mesh their shared narrative of loss and grief alongside the story of her mother’s life. Oddly, IRID feels more ghostly of the two, as it suspends us in the piecemeal stops and starts of the forms of emotion that populate a trauma as it happens—in dementia’s case, extremely slowly, the slowest torture, through which the subject knows less that they are suffering than the caretaker, who can do nothing but stand by and try to make it as easy as they can for the dying mother, while also trying not to lose their own minds. AWS, in counterpoint, breeds the ongoing minutiae with the understanding that begins to arrive as one phase of the story ends—the illness, and the death—and the next phase takes over—the mourning, the wanting to make sense, the madness of grief. AWS feels aboveground, somehow, while IRID is more subterranean, waist-deep in its own terror due to lacking of any pin by which the frame can hold. You never know how long you have until you don’t have any longer, is the problem, partly. The brakes won’t take, and all there ever seems to be is downhill motion, into a pit you understand the shape of—your mother’s body, and her mind, her life—but can’t begin to wrap your mind around without something central, firm, to correspond with—the death itself, and even more so, how you survive it, what you carry forward from it, how life is. By the end of AWS, something of an essence installed into the book’s body, as ink paper, has surely changed through its course, as is often asked of any narrative by those who wish to apply their own values to it, but what that is has no clear nail besides the fact that we can feel it, all the more palpably given the inherent care touched in her sentences and sentiments as the forthrightness with which she refuses to bridge gaps with anything other than the inclusion of the gaps themselves, the tenderness that we can supply from our own understanding, for once, how it must feel, rather than needing to have our stomach filled by what it really isn’t, and never would wish to be. The maze is the map, in a way, and the path is the purpose, and the math is bad, and the way is ours, at once alone and surrounded, open and closed, forward and back.

I find myself now almost exactly where I began: wanting to write about Annie Ernaux and finding myself instead up to my neck in who I am. Any lost sense of electricity learns to remind itself it is still capable of being zapped; that being struck comes out of nowhere, and sometimes all you have to do is want to look. Looking down at my desk, I see the stones I’ve used to force the pages of Ernaux’s book open, so I can type out the quotes I’ve marked in the margins with my pen—always just long straight lines alongside the part I want to remember to return to, never my own words. One of the stones is highly polished and slips easily off the tautened pages unless seated just right onto the crease, maintaining proper balance; the other is a black cube that holds itself still until the other stone slips, causing the book to fall back half shut with the cube stuck in its throat. Later, after I’m finished writing this, I’ll go put it on the shelf with all my other Ernaux books, leaving nothing but the words on its spine as a guide to remind me of my experience of it, until I might open it again. The words will always be the same, no matter when. I’m the one who’ll never be the same.

just bought a copy today! saving this to read once i finish it, super excited

Hell yeah. So glad this exists.